Downrigging has replaced motor mooching as the preferred method of Chinook fishing. Pity.

About 150 feet below the wave-tossed boat, something is toying with the cut-plug herring. It could be a dogfish, for the pesky little sharks are common depending on the season, but it may just as likely be a Chinook.

Nothing happens for several seconds, then the tip nods again. “Give it time.” I am cautious. “There’s lots of room in front, so I just hang on and I’ll power strike when it’s time.”

A few more seconds tick slowly by. Finally the slender tip trembles slightly, dips, then bows slowly toward the water until it is submerged half way to the ferrule. My buddy John twists the throttle and the 16-foot boat leaps forward in response to a 50 h.p. boot to its stern end. “Hit it!” I shout.

I rear back on the long graphite rod as the outboard’s roar is cut and the bow drops. A mass of other boats are bouncing close beside us and to our stern, but there is a clear opening directly ahead. John keeps the bow headed away from the crowd as I reel in my line to avoid any problems.

There are any number of ways that fish can go that will create problems with other anglers, but it chooses to race beneath our boat towards open water. The line suddenly goes slack as it angles up toward the surface, and I crank furiously on the single-action reel to take up the belly of line.

Barely 50 feet off our bow, the surface erupts in a confusion of white spray and flashing silver as a Chinook thrashes about convulsively without actually jumping. Then it sounds, streaking down and away, and there is the staccato sound of whirling handles rattling against fingers. I yelp a curse, who has not used single-action reels and not been occasionally reminded of why they are nicknamed “knuckle busters”?

The fight is typical of a strong, healthy Chinook: swift, diving runs followed by the angler pumping and cranking the sulking fish back up toward the surface. With several repeat performances.

It is a tough, tackle-punishing battle, and eventually, but finally, about 25 minutes after the bite, John nets the beaten fish.

A monster? No, just over 18 pounds. But it had waged a valiant battle against the long, limber rod and single-action reel.

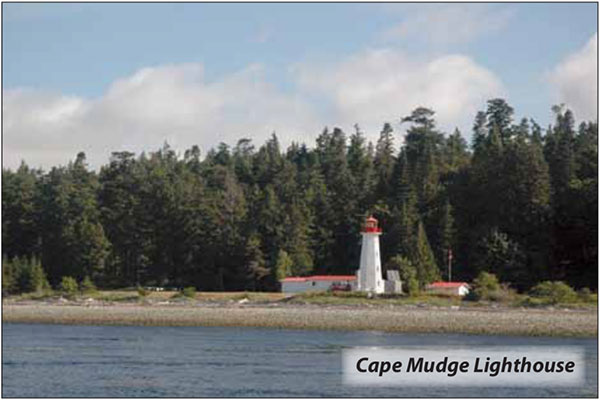

This vignette took place at the Cape Mudge Lighthouse tiderip, one of the most productive Chinook areas in the Campbell River region. Also one of the most popular, as is often evidenced by 50 or more boats operating in an area encompassing 10 acres or so.

Old-timers in the Campbell River area don’t recall seeing mooching practiced until about the early 1940s. Until then, the most popular salmon fishing tactic was trolling, either from small, rowed boats, or larger, motor-propelled craft.

Anglers who use this unique equipment are called “moochers”, which refers to a bait-fishing technique rather than any inclination to borrow or beg. Derived from the slang expression “mooching around”—to move about aimlessly—the term describes the original method of fishing from a free-drifting rowboat. The advent of outboard motors resulted in “motor mooching”, controlled drifting that permits the use of larger boats. This allowed anglers to range further off shore, and to fish in fast-flowing tiderips, where salmon often congregate to feed on baitfish.

The object is to present a bait at the depth where salmon are feeding. Coho are often within 30 feet of the surface, but chinooks may be down 150 feet or more, in which case the bait is lowered to the bottom, then retrieved about 15 feet. If it fails to attract attention, it is reeled up in increments of 10 feet until fish are located.

Rowed mooching is often a solitary endeavor. With the rod in a holder, the angler closely watches the tip while controlling the boat’s drift by rowing. Salmon usually toy with the bait before taking it, so there is ample time to remove the rod and prepare to strike.

Mooching under power is best accomplished with one person operating the motor, while one or two others fish with hand-held rods. Moochers travel light. Aside from rod, reel and line, they require hooks, swivels, a sharp knife, pliers, a stone or small file for sharpening hooks, and a supply of baitfish. Rowers use sinkers of one to three ounces, while those of motor moochers range from four to 12 ounces.

Herring are the mainstay bait, but anchovies and needlefish are also a part of the menu. They are usually fished with two hooks tied in tandem. With the front hook inserted crossways through the nose, while the rear goes through the side, midway between the dorsal and tail fin.

Also popular is a “cut plug”—a baitfish with the head severed at an angle from top to bottom, and beveled from right to left. The angle of either or both cuts alters the bait’s spinning motion: the more angle, the wider the spin; the more bevel, the slower it rotates. The tail hook is threaded through the shoulder, then the front hook is inserted through the top of the shoulder.

Ten to 12 foot graphite rods are a typical mooching rod, of which two feet is handle. The tip is very limber for about one quarter of its length, increasing gradually in strength throughout the centre-section to a stiff butt.

A typical single-action reel holds up to 500 yards of 30-pound test monofilament. All are direct drive, and their collective nickname “knuckle-buster” is derived from the results when fingers tangle with whirling handles as a fish streaks away. An exposed rim on the handle side allows drag to be applied by “palming” the rim during lengthy runs.

Leaders generally test five pounds lighter than the main line, with 20-pound test the minimum for coho, 25-pound for chinook. While five or six feet is often sufficient, some moochers consider 10 to 12 feet minimal. Leaders longer than the rod are avoided, as they make landing of fish difficult.

Crescent-shaped mooching sinkers are either fixed or sliding. As rowed mooching seldom requires more than three ounces, those with swivels mounted fore and aft are popular. However, motor mooching in turbulent water demands heavy sinkers, making sliding models preferable. As a slider moves freely on the main line, the antics of a bulldogging chinook or acrobatic coho simply pulls line through the heavy sinker rather than against it.

Swivels are important. Although a fixed sinker’s shape prevents the main line from twisting, the constant rotation of a cut-plug can twist a leader beyond recognition. Moochers often tie a second swivel between the sinker and bait, while motor moochers may use up to three.

Single hooks are used, and may be matched or mixed in size and style, according to the bait size. One thing is certain: the points must always be sticky sharp.

When the mouthing of a bait transmits up the line, movement of the tip is usually seen before it is felt. Rather than strike, the angler waits—which is often easier said than done—until the limber tip is finally pulled down with authority. The rod’s length then aids in setting the hook, as does the stiff butt, while its overall flexibility buffers the sudden, often violent reaction of the hooked fish.

So, while open admission to mooching might raise eyebrows elsewhere in Canada, to West Coasters it simply identifies you as one who finds the use of long rods and single-action reels the most exciting and rewarding way to tackle two of the gamest fish that swim—coho and Chinook.

Time to try in 2018.