Before we go into detail about what a salmon hatchery is, let’s clear up what a salmon hatchery is not. It is not a fish farm. Most folks who are familiar with fishing and the BC coast might assume that British Columbians know the difference between a hatchery and a farm. The reality is many don’t. Unfortunately, activists who don’t like recreational angling use terms like “industrial fish production” and “hatcheries” loosely to further confuse the public not only about salmon hatcheries, but also about salmon angling and the importance of both to BC.

What is a Salmon Farm?

A salmon farm is like a farm on land, except it’s in the ocean. They are actually called “open net-pen salmon farms,” and they almost exclusively raise Atlantic salmon. Salmon fry that are specifically raised for these farms spend their first year in a hatchery. Then, for an additional two years they are transferred to large pens that are anchored in secluded bays along the BC coast. Farmed salmon never leave the pens except when accidental escapes occur. They feed via an automated system that delivers a prescribed amount of feed until they reach marketable size. Farmers then remove, process, and sell them to markets around the world.

During the growing process, farmers give salmon antibiotics to ward off infection and chemically treat them to control sea lice infestations. In a perfect world, it sounds like a great food production system. In fact, Canada is the fourth-largest producer of farmed salmon and approximately 60% of that production comes from BC. However, this is not a perfect world. Large-scale salmon farming appeared on the coast in the 1990s. Since then it has been the focus of growing controversy and media attention, particularly in the Discovery Islands north of Campbell River and Clayoquot Sound near Tofino. Approximately 120 salmon farms line the BC coast. The federal government regulates the onsite activities, while the province overseas licensing. Opponents want them removed from the ocean and relocated to closed containment land-based facilities. They contend that salmon farms pose a significant threat to wild salmon due to lice infestation and disease pathogen transfer.

What is a Salmon Hatchery?

Salmon hatcheries are entirely different animals. They appeared on North America’s west coast in the 1870s when the first hatchery was built on California’s McCloud River. The first hatchery in BC was constructed in 1883 near Bon Accord on the Fraser River. They were built because salmon stocks began to decline after gold mining operations destroyed spawning beds in the preceding decades. Settlement followed mining, and the habitat damage continued relatively unabated for the next hundred years.

Settlement created demands for living space, food production, and industrial growth to sustain basic needs. It also ushered in an unprecedented period of timber, water, and mineral exploitation, which severely impacted vital salmon habitats. When these conditions intersect with fish needs, the salmon always end up losers. In spite of volumes of regulatory requirements, fines, and penalties at all government levels, basic salmon ecosystem stability and the inventory of productive habitats continued to erode. This set the stage for more hatchery construction.

“Salmon Hatcheries Have Two Principal Purposes.”

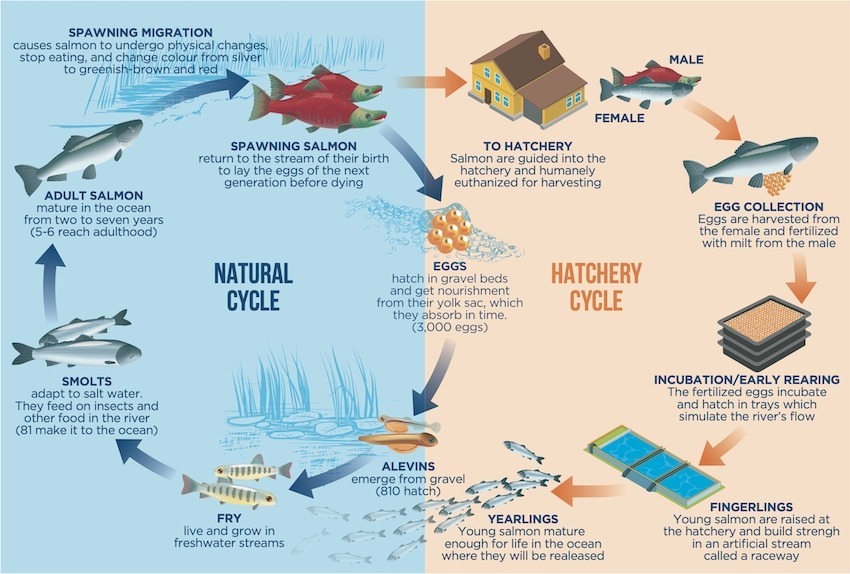

Salmon hatcheries have two principal purposes. The first is to raise salmon to maintain or rebuild salmon populations that have undergone man-made or climate-induced impacts. In their early years, hatcheries were seen as the “silver bullet” for salmon production while allowing the damaging activities to continue. This philosophy persisted until at least the middle of the 1900s.

It took Fisheries Minister Romeo LeBlanc’s Salmonid Enhancement Program to begin to connect hatchery potential with habitat restoration. The second purpose is to produce salmon specifically to sustain or increase harvest. Here are some examples:

- In 1966, Michigan fish managers introduced 658,000 coho smolts to the Platte River and Bear Creek to control explosive alewife populations and restart fisheries on Lake Michigan, and they achieved both goals. Their program was hailed as transformative because it revitalized dying Michigan fishing ports. Michigan’s success prompted the spread of coho, Chinook, steelhead, and pink programs across the Great Lakes and the rebirth of impressive recreational fisheries and economic benefits.

- In Alaska, producing hatchery salmon for catch is referred to as “ocean ranching.” Some of the benefits are assigned to those who are licensed to harvest the returns while the remainder is classified as common property.

- In BC, the process is different than ranching, because hatchery production to support catch is open to all fishing sectors.

What Does a Modern Salmon Hatchery Look Like?

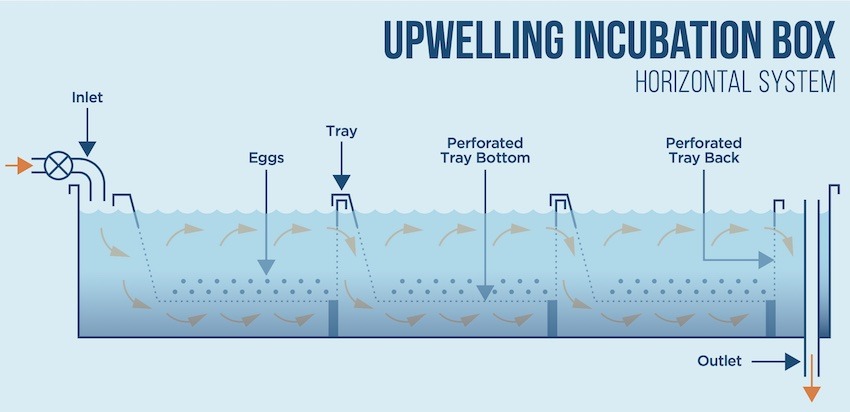

Modern hatcheries have come a long way in 50 years. When Howard English began to restore coho in the Goldstream River near Victoria, his hatchery could fit into the back of a pickup truck. It consisted of a gravel upwelling incubation box with an inflow pipe at the top end, a spawning box in the middle, an outflow pipe at the other end, and a tarp to cover it. In 1982, that’s where I picked up our first batch of fry for the Sidney Anglers Reay Creek Coho Project.

How Does a Modern Salmon Hatchery Work?

Glen Varney from Sooke is experienced in hatchery operations. He volunteered at the original Jack Brooks Hatchery and worked at the government-run Nitinat facility on the southwest coast of Vancouver Island. Peter McCully has been a fisheries technical advisor for southern Vancouver Island for many years. He is based at the Howard English hatchery near Victoria. Both contributed to this technical explanation of exactly how a modern salmon hatchery works.

A Basic Hatchery Includes the Following:

- A consistently reliable source of clean cold water. It should be screened at the intake to capture any debris that could enter the water system.

- The clean water flows to a settling tank before passing through a series of filters that go from coarse to fine.

- The water is then aerated to increase the oxygen levels before entering the hatchery.

- The water flows to a distribution system that directs it towards incubation trays and holding tanks.

- Each location that receives clean water has its own separate outflow so the water does not contaminate operations further along in the process.

- The water used for egg incubation systems and holding tanks passes through a second settling pond and filtration process before it flows back into the stream from which it was sourced.

What Do Hatchery Workers Do?

Hatcheries are usually situated near a salmon-bearing stream with stocks that need enhancement. However, they also act as satellite facilities for rivers and creeks in regions where salmon and trout stocks are in trouble. In fact, if transport logistics were not an issue, a hatchery located on the coast could satellite for weak stocks from an interior BC stream.

Late summer, fall, and spring are the busiest times for hatchery crews. The activity matches the spawning and fry development cycles of salmon. Crews begin when the first fish arrive in the rivers in late August. In other cases, they swim right into the hatchery or are manually removed from the river using fine mesh landing nets.

Sometimes the broodstock is captured at a barrier, called a fence, that prevents fish from moving upstream. Fences are erected just before the salmon runs start and are removed ahead of high water flows to prevent them from blowing out. Aside from providing an efficient means of capturing fish, they also facilitate reasonably accurate escapement counts. The data goes to DFO. For example, the 2020 fence count on the Cowichan River the Chinook was 9,192 Chinook consisting of 5,648 adults and 3,544 jacks. Because Cowichan fence data has been collected for years, and the Chinook run timing is known, the fence count helps DFO in estimating a total run size, even if no further counts are taken due to poor visibility or high water conditions.

After the adults are captured, they are transported to the hatchery, where they are held in circular tanks or long concrete raceways until they mature. The egg take process begins when the first females are ready to drop eggs. At this stage, the females are killed and the eggs are removed and fertilized with milt from males.

Males in good condition are returned to the tanks so they can fertilize eggs taken at a later date. This actually mimics what goes on in the river, where the females die soon after spawning while the males continue looking for other females to mate with.

Staff immediately place the fertilized eggs in heath trays where clean, cold, oxygenated water passes through them to keep the eggs alive during the incubation period. Depending on the species, each tray can hold 5,000 to 10,000 eggs. These trays produce a much higher survival rate than natural spawning conditions. The egg take continues until the hatchery either hits its egg quota or runs out of broodstock.

In many systems, staff return the carcasses to the river where they provide an immediate food source for bears, eagles, wolves, and other land and water-based creatures. These carcasses also boost productivity by fertilizing these often nutrient-depressed streams. At some of the bigger hatcheries, local First Nations take the surplus salmon in what is known as an ESSR (Escapement Surplus to Spawning Requirements) fishery.

During the incubation period, hatchery employees make sure the incubation systems are working and clean. This helps to maximize the number of fry that emerge in the spring. At the fry stage, the tiny salmon are moved to larger holding tanks where, depending on the species, they remain for varying lengths of time.

Then, hatchery staff release the fry directly into the adjacent stream, or transport those from other systems back to their natal streams for release. Significant numbers are designated for educational purposes under programs like Salmonids in the classroom. Fry from hatcheries are also regularly used to re-establish populations in barren streams that either never supported salmon or had their own runs wiped out.

Under some conditions, salmon fry remain in the hatcheries for longer periods of time. For example, coho are kept in facilities for as long as a year until they reach the pre-smolt stage. Then hatchery staff take them to release sites to acclimatize and imprint before migrating to sea. The goal is to get much higher fry-to-smolt survival rates. In cases where runs are approaching extinction levels, fry are kept in the hatchery until they reach spawning maturity. This is called a “captive broodstock program.” The theory is to rear fry to maturity and then use these fish as the primary broodstock. This provides the system with a huge boost in egg, fry, and smolt output compared to releasing the same number of salmon into the wild. The downside is cost associated with growing salmon for up to 4 years in captivity.

Hatcheries also perform other valuable duties, including adipose fin clipping. Clipped adipose fins differentiate hatchery salmon from wild salmon. Then coded wire tags (CWTs) are implanted into the heads of fin-clipped fry to identify which hatchery they came from. DFO has set up CWT head recovery programs for public, commercial and First Nations fisheries. The Department of Fisheries also gets CWTs from tagged fish that return to the hatcheries. The tags provide a wealth of data that is critical for developing salmon management policies and understanding the life cycles of various species and stocks.

Education and community outreach are vitally important to explain to the public just how valuable salmon are to the Province’s coastal and interior communities, and to the maintenance of freshwater ecosystems. Not only do hatcheries provide salmon for class- rooms, but they also engage their communities by using local volunteer workers, educating those workers, offering open houses for the general public, hosting special salmon-related events, and jointly engaging in research work with secondary and post-secondary institutions, as well as government and private fisheries research entities.

Conclusion

The salmon hatchery story includes a hundred years of success and failure prior to finally developing technologies that come close to mimicking natural conditions. It is also full of endless debates and studies about whether hatcheries benefit salmon or not. Hatchery technology has come a long way from the late 1800s when Sam Wilmot, Canada’s leading authority on fish culture, believed that Pacific salmon were all the same species and did not die after spawning, according to Geoff Meggs in his book The Decline of the British Columbia Fishery.

We have reached a critical stage in the larger salmon debate, which includes deciding what role hatcheries will play in salmon recovery and sustaining fisheries. I think it’s time that these polarized debates and studies took a back seat to a pragmatic and forward- thinking approach to hatchery utilization, or face what I see as inevitable and disastrous consequences for salmon.

Both Peter McCully and Glen Varney are unequivocal that modern hatchery technology is absolutely required to sustain salmon stocks. According to McCully, “Small community-operated hatcheries are conservation-based and ideally suited to the watersheds they support. They are operated by people with local knowledge … something for which DFO is tone-deaf. Varney adds that we have never really repaired salmon habitat, and with climate change we have no choice. Hatcheries will need to continue.”

Many of the same human-driven pressures continue to erode the basic needs of salmon and the resilience of salmon habitats, in spite of regulatory measures to mitigate these activities. Furthermore, these problems are now accelerating due to climate change, as Varney notes.

Whether we have hatcheries or not might be irrelevant in 50 years, given the downward trajectories of important salmon stocks, it seems to me we are past the point of relying on habitat restoration and nature to rebuild stocks for many parts of the province.

The benefits that hatchery technologies currently offer, with the promise of more advances to come, suggest strongly that the hatchery role is a complementary, strategic, and necessary foundation for salmon recovery.

This article appeared in Island Fisherman Magazine. Never miss another issue—subscribe today!

This article appeared in Island Fisherman Magazine. Never miss another issue—subscribe today!

No hatcheries. stream rehabitation is the best way to bring back the salmon.

Fisheries and forestry have to work together, it is that simple.

How is that working for you so far…..it’s not

Disagree, go and look at your local river