Many people, especially beginners, find it baffling when they start looking at lines and rods and reels in combination with another. It is not all that complex once you understand what controls how they all fit together. The type of rod and reel we buy is dependent upon what “weight” of line we are using. Line weight and function controls everything in terms of the rest of your tackle.

The vast majority of fly lines are about 25 metres (75 feet) long and come in various weights, tapers, functions, and colours. Depending upon where you are fishing, what you are fishing for, and how you want to fish, all of these factors must be considered.

Fly Line Construction

Line Construction

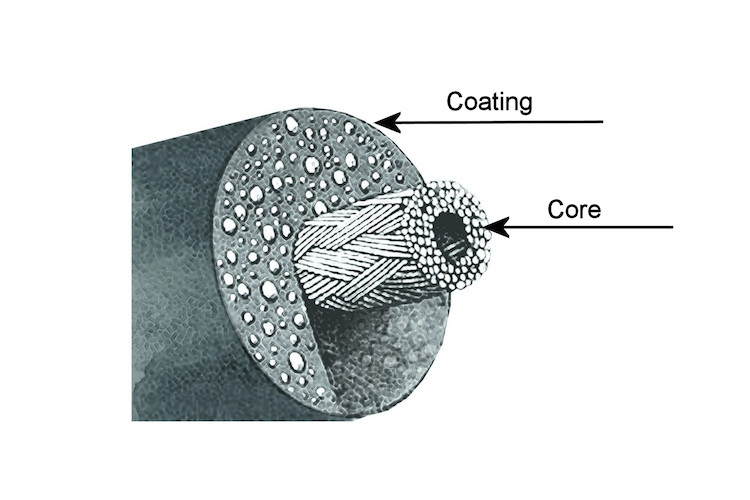

Most modern fly lines are constructed from vinyl material that forms the coating with a strong core in the middle. The vinyl coating is supple and will break if you try to tie leader or backing directly onto it if the line has no core. The core is tougher and allows the angler to knot to the fly line. Just as important though, the core controls the line’s strength, stretch and stiffness.

All fly line cores are designed to be stronger than the heaviest tippets that would normally be used with them. Line stretch is important, because if there is too much stretch the line will be too floppy and tough to cast. Not stretchy enough, and it will have memory problems where you can’t get the line to straighten out; it will retain its loops like a coil spring when stripped off the reel. Stiffness is in many ways similar to stretch, but stiffness is targeted more at making the line the right stiffness for the temperatures that you will be fishing. Hot temperatures can cause some lines to become too supple, and so they will get too floppy to cast well, while cold can cause lines to get too stiff and again develop memory problems.’

Some lines (some clear intermediate sink lines in particular) have no core, and so you cannot knot directly to them—you have to either use a leader loop or a whipped loop.

Fly Line Weights

Fly lines must be heavy in order to get the fly out any distance from the rod tip, and thus they have weight.

Line weight designations range from 1 to 15, 1 being the lightest and 15 the heaviest. These numbers are simply a relative scale of weight and do not indicate the actual weight of the line. Each number does, however, represent a standard weight in grains for the first 30 feet of the fly line as established by the American Fishing Tackle Manufacturing Association (AFTMA). (For example, the first 30′ of a 6wt fly line should weigh between 152-168 grains, with the optimal weight being 160 grains.)

Fly Line Labels

Beginners should concern themselves with weights 5 through 9; these are the line weights most commonly associated with trout, bass, pike, steelhead, and salmon fishing. For trout fishing you should consider weights 5 to 7; steelhead fishermen will want to consider lines 7 through 9; and salmon anglers will want to use weights 6 through 15 depending upon the species. The best all-around line for the beginner is a 6 or 7 weight, 6 if you want to fish strictly trout and pink salmon, 7 if you want to try steelhead or coho salmon as well.

Fly Line Taper

Line Taper

Most fly lines are comprised of tapered parts: the tip, front taper, belly, rear taper, and running (shooting) line. The tip is narrow and delicate for presenting the fly softly. The front taper tapers from thin to fat to roll over the cast smoothly and evenly. The belly is heavy and carries the line out. The rear taper tapers from fat to thin. The running line is thin and light so it can be pulled forward by the front taper and belly, for distance casting.

Fly lines come in a variety of tapers: level, double taper, weight forward, and shooting taper. A level taper line is designed, as the name implies, to be the same diameter from end to end. It is, generally speaking, the least expensive of the fly lines but has limited use. Double taper and weight forward are by far the most commonly used lines, and the beginner should choose one of these two tapers.

Double taper lines begin thin at one end and taper to their maximum diameter within about 7 metres (25 feet). The diameter remains the same over the centre 7 metres or so and then tapers back down to thin again at the other end. The two end tapers are mirror images of each other. Because of the even distribution of weight over the length of the line, double tapered lines allow the fly fisher to make delicate presentations of the fly without disturbing the water too much. It also has the added advantage of being reversible. Since both ends of the line are tapered the same, when one end wears out the angler can reverse the line and continue to use it. Double taper does not, however, offer the caster the option of long distant casts; weight forward does, but if you fish clear “skinny” water with spooky fish where delicacy takes precedence over distance, then double taper is the line for you.

Weight forward taper sacrifices deli- cacy of presentation for distance. The line is designed to taper very quickly to its belly and then quickly taper back down to a thin shooting line. This distributes the majority of the weight in the line into the taper and the belly (the first 10 metres). The first 10 metres is cast by the rod and caster and the shooting line simply follows the head out onto the water when the cast is released or “shot.”

There is also a specialty weight forward line called a shooting taper or shooting head. It is a specialized line about 10 metres in length that incorporates the taper of a weight forward with- out any shooting line. Dacron backing is tied to the butt and the line is virtually hurled out over the water much like a spincaster hurls his lure. It is designed strictly for distance casting and begin- ning fly-fishers need not concern themselves with it. That’s all there is to line tapers … not too complex, really.

Fly Line Functions

Fly Line Density

Line function is a simple thing: The line is designed to either float or sink or do both at the same time. Thus, we have three function designations: floating, sinking and floating/sinking (commonly called sink tip).

Dry Lines

Dry/Floating Lines Table

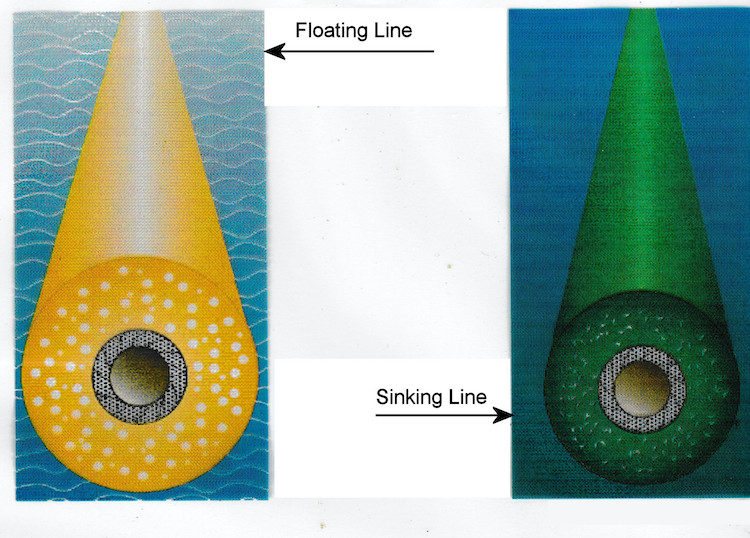

Dry lines (or floating lines) are the simplest; they simply float and there are no subdivisions of this function. Floating line is used when fishing dry flies and can also be used to fish wet flies or even nymphs if the water is shallow enough. Floating lines float because their vinyl coating is impregnated with air bubbles; if you cut it open it looks like the inside of an Aero chocolate bar.

Sinking Lines

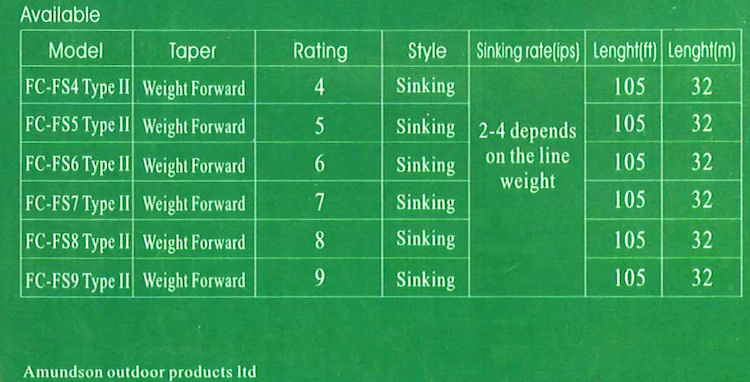

Wet/Sinking Lines Table

Wet lines (or sinking lines) are designed to sink. They sink because their vinyl coating is impregnated with tungsten chips; the more tungsten chips per inch of line, the faster it sinks. Thus, sinking lines have varying sink rates.

The sink rates vary in name between manufacturers, but generally speaking are as follows: slow (or intermediate) sinking, Type I Sinking, Type II Fast Sinking, Type III Extra Fast Sinking, Type IV Hi- D, Type V Super Hi-D, and lead core. The actual rate at which these lines sink varies between 1.5 inches per second to 6.0 inches per second or greater. To get a good idea of the actual sink rates pick up some manufacturers’ catalogues. For the beginner I recommend a fast sinking or extra fast sinking fly line. These two will perform admirably in most wet line situations.

Besides the standard sinking lines, companies have developed what they call a level sink line. In a standard wet line, regardless of the sink rate, the tungsten chips are distributed evenly throughout the vinyl coating of the line. Because the line tapers towards the end, though, there is not as much tungsten in the tip as there is in the belly. The tip does not sink as quickly as the belly, so you get a belly or “U” in your line as it sinks, and the longer you allow it to sink the bigger the “U” belly gets. Level sink line has more tungsten per inch in the tapered portion of the line, and so it sinks more evenly across its length. This can allow the angler to get their fly down to the bottom at the same time the rest of the line gets there, instead of the belly hitting the bottom before the fly gets close. Sometimes you want that and other times you don’t, depending on the type of insect you are trying to imitate.

Line Box Covers

This article appeared in the May 2019 Issue of Island Fisherman Magazine. Subscribe today and never miss an issue!

Visit the Store

$34.99

$34.99

Featured Catch

Joel Unickow halibut (Photo: Rob Frawley Lucky Strike Sportfishing Tofino)