-

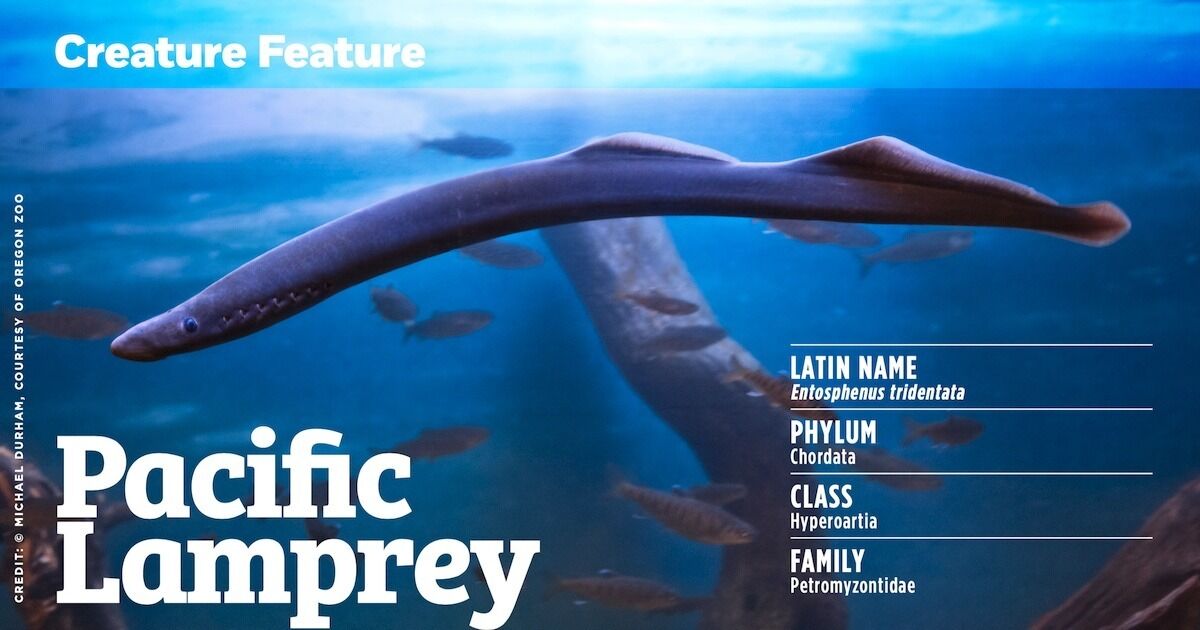

Latin Name: Entosphenus tridentata/tridentatus

-

Phylum: Chordata

-

Class: Hyperoartia

-

Family: Petromyzontidae

Where Do Lampreys Live?

Lampreys are one of our planet’s most ancient species, turning up in the fossil record at least as far back as 400 million years ago. They pre-existed dinosaurs, and probably even trees. They are anadromous, meaning they spend part of their lives at sea, and return to freshwater to spawn. They have been found far inland, in high mountain streams, and far offshore, from the surface to depths of 1,500 m (5,000′). The Pacific lamprey’s native range includes most of the streams, rivers, and seas of the Pacific Rim, from Russia to Japan and Alaska to Baja, with the highest concentrations along the northwest coast of North America, especially the Columbia River Basin. But although it somehow managed to survive three ice ages and five mass extinctions, the past 100 years have seen it completely disappear from a majority of its historic freshwater habitat.

What Do Lampreys Look Like?

Lampreys look like eels and swim like eels, so much so that they have been called eels, time out of mind. But in actuality, these bizarre prehistoric fish are not even related to eels. In contrast, they lack scales and don’t have paired jaws or fins. They are vertebrates, but their skeletons are made entirely of cartilage rather than bone. Our Pacific variety has a slender, elongated body that grows to about 2 1⁄2′ and has two dorsal fins, a tiny anal fin, and a tail fin that is larger on the bottom than on top. It breathes through seven pairs of gill slits along its sides. In the ocean it has a deep green or blue back and pale underside, while in freshwater, it is brown.

But here’s where it really starts to get weird. In addition to the two ordinary blue eyes on the sides of its head, the adult has a “third eye” on top of its head, for sensing light and darkness, and a nasal pore for smelling. Instead of jaws, the lamprey has a powerful suction cup for a mouth, complete with circular rows of sharply pointed teeth. There are three sharp teeth in the middle which bear a distinct resemblance to viper or vampire fangs. This is no accident.

Pacific Lamprey using its suction-cup-style mouth to attach to rock. Photo Credit: Conrad / Adobestock

What Do Lampreys Eat, What Eats Them, And What Else Kills Them?

During its time in the ocean, the lamprey attaches itself to other creatures, such as whales, sharks, seals, and large fish. It rasps away skin and scales with its tongue to create a little hole through which to suck blood and fluids for a time, then lets go and moves on, almost never doing any permanent damage to the host—aside from the odd, round scar. If lifted out of the water, the lamprey will detach itself to avoid suffocation. This is likely one reason for breaching behaviour in whales and basking sharks.

Pacific Lamprey Photo Credit- CASCOLY2 : ADOBESTOCK

A majority of the lamprey’s existence is spent as an eyeless, larval ammocoete. In this stage, it is a filter feeder that burrows into the soft stream or river bottom and then draws in the overlying water to suck out the food it needs—a mixture of algae, plant material, and feces from fish and insects. In this way, ammocoetes act as stream-cleaners.

Lampreys are an important seasonal harvest and ceremonial food for many native tribes. For millennia, both adults and larvae also have provided many fish, birds, and mammals with a reliable, high-fat food source, thereby reducing predation pressure on adult salmon during their spawning migration. And like salmon, they play an important role in transporting nitrogen and other nutrients into freshwater ecosystems.

Human infrastructure—particularly dams and chemicals that degrade water quality—is thought to be the main cause of the lamprey’s decline. Lampreys can attach to almost any wet surface, but sharp corners tend to break their suction, especially in swift water, and they struggle with fish ladders designed for salmon. But we can fix many of the problems we have created, and several tribes of the Columbia River Basin have begun the restoration process, with collaboration from governmental agencies. This involves removing some dams and modifying others, or installing structures that allow for lamprey passage. Many lampreys have been caught, raised, and relocated successfully to spawn in depleted streams above the dams, where they gradually rebuild their habitat and return health to the stream.

How Do Lampreys Grow And Reproduce?

Their spawning journey starts in mid-summer and takes a year or longer, during which they do not eat. They use their suction-cup mouths to grab onto rocks in riverbeds and waterfalls, and are capable of wrapping their bodies around objects to move them or manoeuvre themselves into a more favourable position. They also can swim backwards.

It is unknown whether or not they seek their natal streams or use other cues to determine a good location, but they tend to choose habitat similar to salmon and trout. When they arrive at their destination, each female builds a pebbly nest (called a redd) and deposits 100,000-300,000 small, beadlike eggs into it. The male then fertilizes them. Both parents die within about 4 days of spawning, and quickly thereafter they decompose, fertilizing the streambed.

After hatching, the ammocoetes spend 3-7 years blindly cleaning the freshwater substrates until they reach adulthood, grow eyes, and head out to sea. The parasitic, oceangoing phase lasts 2-3 years, before they are ready to complete the cycle. They live up to 11 years.

Lamprey Trivia

The northern lampreys of the Petromyzontidae family—including the Pacific lamprey—have between 164 and 174 chromosomes— the highest number of any vertebrate. Contrast that with humans, who have only 46 (in 23 pairs).

The Pacific lamprey gets its Latin name from its three prominent teeth, which also cause it sometimes to be known as the “three-tooth” or “tridentate” lamprey.

One of the traditional creation stories of the Columbia Basin tribes says that Lamprey Eel was an avid gambler who didn’t know when to stop. He talked such a big game that once, when he was gambling with Coyote, he ended up gambling away his arms and legs. Coyote said, since his mouth got him into such trouble, he would have to use it like a hand to move things, and like legs to help him move around. While it was so busy doing the job of arms and legs, it wouldn’t have time to talk and brag.

First Nations And The Lamprey

In indigenous cultures, lampreys have had many uses. Typically, they are caught by hand at waterfalls or rapids where the current forces them to attach to rocks and rest before moving up-stream. Because they are so fatty, there is a tradition of feeding them to babies and growing children. Healers collected the fat that dripped off the “eels” as they roasted over a fire and used it to make lamp oil and medicine.

Elmer Crow Jr. of the Nez Perce tribe, who spearheaded rehabilitation efforts in Idaho, said, “The lamprey is our elder. Without him, the circle of life is broken.” And this is true. Not only are the various species of lamprey pivotal to the viability of our riparian ecosystems, but people have had a relationship with them since antiquity. Likely the earliest humans recognized them as a food source. The writings of Plutarch and Seneca contain anecdotes of Romans who kept lampreys for pets—and also gruesome punishments. Among the wealthy in Europe, lamprey have been prized as delicacies for hundreds—possibly thousands—of years. Their meat was coveted especially during Lent, because it resembled beef more than any other fish. British records allege that King Henry I died of eating too much lamprey pie. More recent pop culture has Tyrion Lannister eating lamprey pie in Game of Thrones, season two.

So, it’s really true that some things never change, not in a million years—not in 400 million years, as long as we don’t mess with them too much, and we make the effort to repair whatever we’ve damaged. And, considering the amount of discomfort lampreys have dealt out over the aeons, that is a surprisingly comforting thought!

2 Comments

Leave A Comment

Visit the Store

$34.99

$34.99

Featured Catch

Joel Unickow halibut (Photo: Rob Frawley Lucky Strike Sportfishing Tofino)

Interesting article on the Pacific lamprey. How do these differ from the Pacific hagfish – are they related (as they look similar)?

David

Thank you! They differ in a number of ways, and are not closely related, although they are both ancient and have a similar body form. Hagfish generate copious slime and don’t have stomachs, live on the bottom, and aren’t anadromous (meaning they spend their whole lives in the ocean environment, rather than traveling inland to spawn). These are just a few of the differences. I will put Pacific hagfish on my list of creatures to investigate further. I appreciate the idea!