Most of us have been testing our downrigger wire voltage since we started fishing—or at least we think we have. As a commercial troller, I did my testing in the same manner, and believed the results. We have been told right from the start that the voltage was real, and the belief was passed along and expanded to such a degree that it became gospel. It is easy to see why: You can physically see the voltage on your meter. It wasn’t until I started developing my voltage tuned lures that I began to question the validity of the test.

How To Do A Downrigger Test

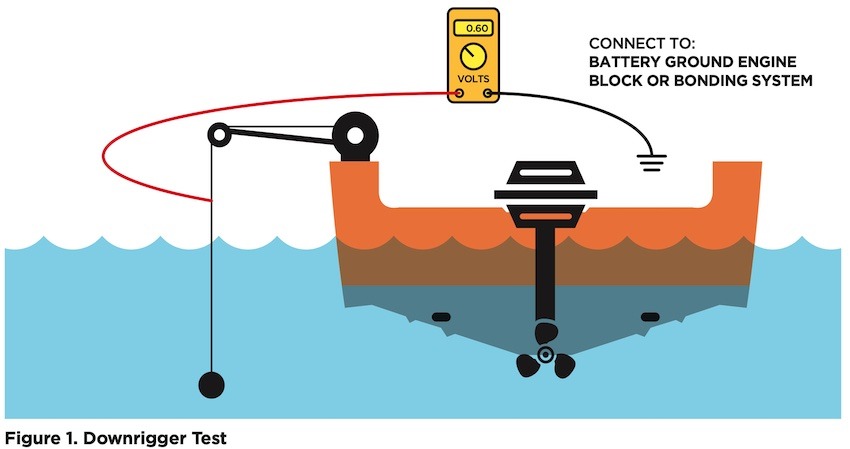

Let’s start with a description of how we normally do the test (Figure 1).

Use a multimeter set on 2 volts DC, or DC volts, depending upon the meter. Lower the downrigger weight into the water and let down some wire. Connect the negative meter probe to the battery ground, engine block, bonding system, etc. Then you touch the positive probe to the trolling wire above the surface of the water. Now check the meter reading, and that is your wire voltage, right? Actually, that’s wrong. It is impossible to create voltage on your trolling wire in this manner. To start with, science doesn’t support it. No voltage-creating cells exist where there is no conductive pathway. By a conductive pathway, I mean a mechanical connection, like a copper wire or a load such as a light bulb, and to a lesser degree, even a voltmeter. Once you have a pathway, the current can then use the electrolyte (water) as the return path. But it cannot flow through the water for both pathways.

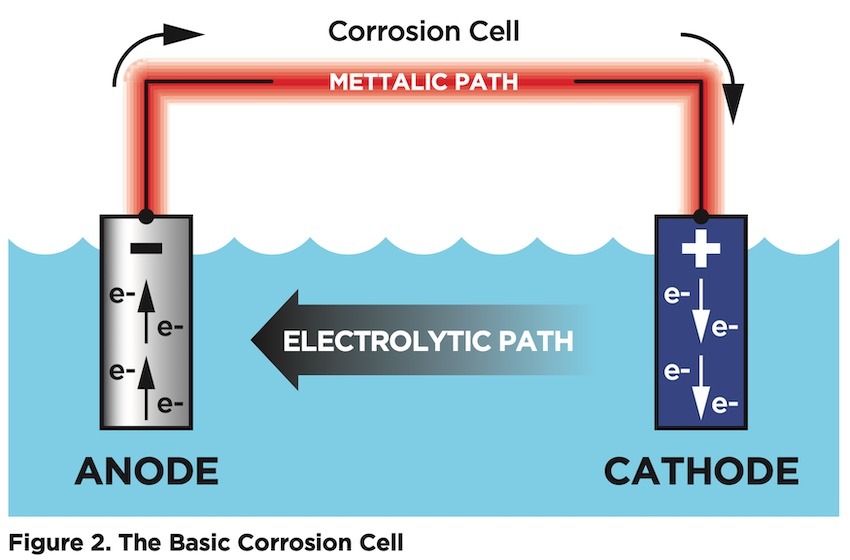

There are two basic cells. One is a galvanic corrosion cell (Figure 2), which is how your underwater boat metals are configured. The metallic path can be a wire, as shown in Figure 2, or where the metals are connected together, like a zinc anode bolted to the metal to be protected (cathode).

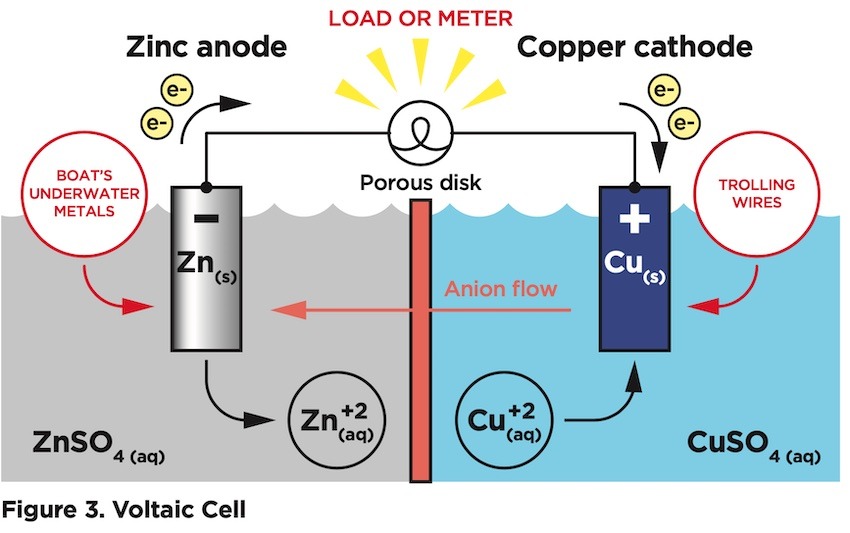

Figure 3 shows a voltaic cell, which is essentially a common car battery.

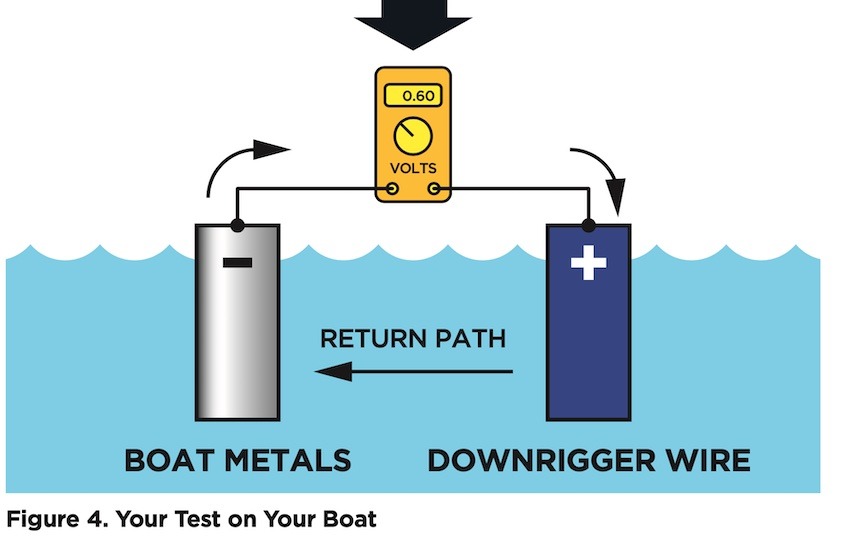

You will see that I have added a multimeter to Figure 4.

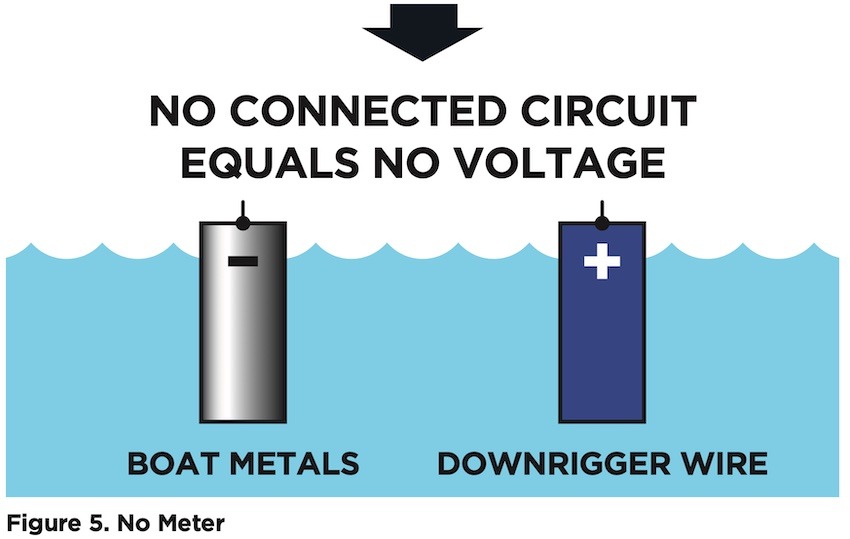

This represents and replaces the load, and when the meter is connected, it completes the circuit. But when I remove the meter (Figure 5), there is no circuit. Follow the sequence of the following 3 diagrams, and do a mental comparison to your boat and downrigger wire.

To put it in lay terms, what happens when you put your aluminum-framed fish net into the water to scoop a fish? Or a metal pike pole? They are the same distance away from the boat, and isolated just like the trolling wire is. Do you think that you are creating voltage on those? Let’s take that to the next level. What happens when you tie up to a metal buoy or another boat? Every marina would be a caustic stewpot if voltage were created in this manner. It’s as ludicrous as saying “My zincs are close to my boat metals, so they are protected.” It just doesn’t work that way. No contact means no voltage, period.

I debated this quite extensively with an Alaskan commercial troller. He actually helped me to make my case by telling me that one spring during haul out, he didn’t clean his copper cooling pipes well enough before clamping his new zincs to them. A year later, he discovered that his zincs were virtually untouched, when they should have been depleted by more than half. Corrosion and voltage go hand in hand. Zincs (anodes) have to corrode in order protect the more proud metals, and a byproduct of the corrosion is positive voltage.

The next time that you want to check your “downrigger wire voltage,” as in Figure 1, do your normal test, and then simply drop the positive meter probe into the water beside the boat. Your reading will be very close to that of the stainless wire. So, what are you actually reading? There are two ways to describe it.

The simplest explanation is that you are (inaccurately) measuring your hull voltage, not the wire voltage. All that the stainless wire represents is an extension of your meter probe. In fact, if you had a foot or so of trolling wire attached to your positive meter probe and touched it into the water, the reading would be the same as lowering the downrigger wire into the water a short distance and measuring from that. If there happen to be other metals, like brass crimps, attached to your downrigger wire, there may be some small voltage differences.

The more accurate description of what you are reading is that you are measuring the difference in the galvanic rating of the two metals or groups of metals. One group

is your accumulated and connected boat metals, including zincs (anodes).

Zincs

The other group is the stainless downrigger wire, or the nickel plating on the meter probe when it was dropped into the water. The nickel plating and the stainless wire have similar ratings as per the galvanic scale (series), resulting in similar readings. If you used copper, steel. or aluminum as examples, as extensions of your meter probe (reader wire), you would see different voltage readings from each. So, if you were simply measuring the voltage on your downrigger wire, it wouldn’t matter what metal you used as the reader wire, but seeing as the voltages all differ, this should tell you that the galvanic rating for each metal is what determines the voltage that you are reading on your meter.

So, should you despair that you don’t have downrigger wire voltage? Not at all. Your boat’s voltage signature in water is more important than wire voltages. Most people don’t understand how far a boat’s voltage signature can travel in water, and how much the fish are affected by it. Here’s what I always ask anglers: “Have you ever owned or known of someone who has owned a boat that simply doesn’t catch fish?” I think we are all aware of that phenomenon, but think about it. That boat still can’t fish even down at depths of 200 feet and beyond. That should tell you just how much influence that the boat has on fish and your rate of success. If the negative signature of a boat has that much of a repelling factor, then a positive signature will have just as much of an attracting factor on fish.”

If you are one of the anglers who still uses a “black box” or Ion Control Cannon downrigger to apply voltage to the downrigger wire, and if you have a strongly negative boat signature, chances are that the positive wire voltage will not overcome what the boat is giving off. I have seen this phenomenon many times with customers of my voltage-tuned products. When the boat is strongly negative, very little will help. The boat needs to be fixed before you will see improvements to your catch rate. For those who missed it, check out my article from last issue.

Al Dampier was the in the inventor of Lurecharge.ca This article appeared in Island Fisherman magazine. Never miss another issue—subscribe today!

Visit the Store

$34.99

$34.99

Featured Catch

Joel Unickow halibut (Photo: Rob Frawley Lucky Strike Sportfishing Tofino)