As bodies of water go, Discovery Passage isn’t particularly large. It stretches approximately 23 nm or 43 km from Chatham Point in the northwest to Cape Mudge at the bottom end of Quadra Island to the southeast. Named after Captain George Vancouver’s ship H.M.S. Discovery, Discovery Passage is bordered on the mainland side by Quadra, Maude and Sonora Islands, and on the other side entirely by Vancouver Island.

More important is its location near the end of the tidal flow from the open Pacific Ocean around the top end of Vancouver Island, where the flow enters the Strait of Georgia via Queen Charlotte and Johnstone Straits and then Discovery Passage. Somewhere between Campbell River and Courtenay/Comox the tides meet, with everything southeast of that point influenced by the tidal flow around the opposite end of Vancouver Island and through the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Seymour Narrows and Ripple Rock

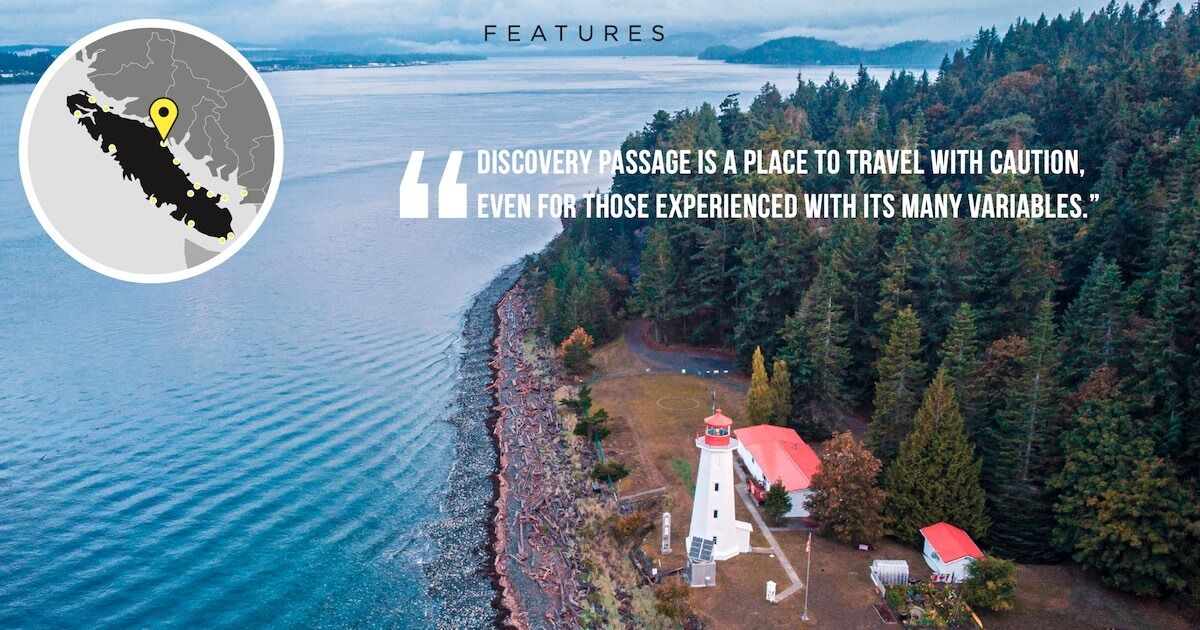

The consequence of this geography is that a truly vast amount of water travels through Discovery Passage in both directions twice a day as the tides flood and ebb. The relatively narrow width of this passage translates into some of the fastest tidal flows in the world, most particularly in the area of Seymour Narrows—location of the infamous Ripple Rock, or what’s left of it after the world’s largest non-nuclear explosion in 1958. And the consequence of this is that for boaters, Discovery Passage is a place to travel with caution, even for those experienced with its many variables.

Photo Credit: Ripple Rock explosion catalog number 19984-3 courtesy of the Museum at Campbell River

For visiting boaters on Discovery Passage, the next thing to consider is not so much the tide table at Campbell River (although that is important) but rather what the current table reads for Seymour Narrows. Although there’s only 7 nm/13 km between the two locations, the Narrows has a separate section that shows not only when each flood and ebb tide begins, but—and most importantly—when and at what speed the peak surge is calculated to occur. The flood tides, heading in the direction of Vancouver, are always slightly quicker than the ebbs, and the fastest tides of 2021 are May 27 and December 5 with a speed of 15.7 kts. Peak speeds on both June 24 and 25 are projected to be 15.6 kts, approaching 30 km/h!

The “Boiling” Seymour Narrows

Most readers of this magazine will have boats that plane and ordinarily travel at a somewhat greater speed than even the fastest tides in Seymour Narrows, but that is no reason to be complacent when boating in this area. As the tide pushes along in either direction, local geographic structure causes tidelines to form, breaking away from the shoreline. On any tide over half the maximum speed in Seymour Narrows, these tidelines are characterized by whirlpools that spin along, up to several metres across, setting up in an instant, disappearing, and then re-forming just as quickly. Back eddies, or counter- currents, form on the inside of the tideline away from the main current, and in the larger back eddies—not restricted just to the Seymour Narrows area—“boils” occur. These are large fists of water that literally boil up, essentially a vertical version of whirlpools which form on a horizontal plane.

Major Tidelines, Seymour Narrows Area | Ebb Tide

Major Tidelines, Seymour Narrows Area | Flood Tide

Tidelines

Traversing these tidelines demands the utmost vigilance by boat operators, not just because of the irregular and frequently changing nature of the water in front of one’s boat, but also because this is where debris collects, trapped between currents going in opposite directions. Logs, especially those that have become waterlogged, often sit subsurface (or nearly so) and hitting one in these already turbulent waters can be a frightening experience. To minimize the chance of this occurring, don’t ever travel along tidelines. Choose what looks like a safe spot to cross the tideline, and then deal with the water conditions on the far side.

Wind Against Tide

Even those of us with considerable experience on these waters can get caught out. In mid-March 2021, I went fishing with my friend Harley out wide of Cape Mudge late on an ebb tide that was flowing towards the top end of Vancouver Island. It had been blowing steadily southeast 15-20 kts—not ideal but fishable—with wind and tide going in the same direction. The weather was forecast to go back to a westerly wind about the time we intended to get off the water but it changed early, fast, and hard—literally—as we were travelling to the Hump. I dropped a line and turned around to talk to Harley, who immediately commented that conditions were deteriorating quickly with rapidly building seas. I noticed a strike and hooked a sub-legal Chinook. In the time it took to reel it in and release the fish, conditions went from bad to worse, the temperature dropped, and it started snowing. It was a brutal ride against standing waves in my 8 m Grady White over the 2 miles from the Hump to the lighthouse at Cape Mudge where the water conditions improved somewhat— I could only make 7 kts speed over ground, “shovelling” green water over the bow with the spray freezing to slush on the windscreen. With more than 90 years (yikes!) of boating experience between us, we agreed it was one of the worst boating experiences we could remember.

Although there are many locations with tidelines in Discovery Passage that could cause problems for unwary boaters the following are the most important to be aware of:

- Maude Island Red Light (Seymour Narrows)—both ebb and flood tides, also the Overfall towards Yellow Island on the ebb tide

- Seymour Narrows Green Light (VI shore)—both ebb and flood tides and Sea Lion Rock (between Green Light and Browns Bay) on the ebb tide

- Race Point—both ebb and flood tides

- Quadra Island near Quathiaski Cove—ebb and flood tides

- Cape Mudge, SW corner of Quadra Island—flood tide

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a search through home videos on the Seymour Narrows area on YouTube is worth even more. These tidal conditions are not unique to Discovery Passage. All three sets of tidal passages adjacent to Stuart Island at the entrance to Bute Inlet—Arran, Yuculta, and Dent Rapids—have fearsome flows, as do the nearby Hole-in-the-Wall or the Skookumchuck Narrows entering Jervis Inlet. Keep your eyes wide open and stay safe when travelling these waters!

This article appeared in Island Fisherman magazine. Never miss another issue—subscribe today!

Visit the Store

$34.99

$34.99

Featured Catch

Joel Unickow halibut (Photo: Rob Frawley Lucky Strike Sportfishing Tofino)