Monkey Creek is a small stream that flows into Quatsino Sound on the northern end of Vancouver Island. This is remote country with wild streams and wild salmon. Even so, these watersheds have felt the impact of salmon harvest excesses and industrial encroachment.

The west coast of Vancouver Island was ground zero for a lengthy salmon war between Canada and the US, one that was not resolved until the signing of the Pacific Salmon Treaty in 1985. Prior to the agreement, Canada’s commercial fisheries intentionally overfished salmon bound for the northwest US. This was in retaliation for Alaska’s overfishing of Canadian salmon, and for US interceptions, primarily of Fraser River Sockeye. Unfortunately, important west coast Vancouver Island salmon stocks, particularly Chinook, were caught in the crossfire. This inevitably depleted spawning escapements.

The northern half of the island has also seen its share of industrial activities, like logging and mining, which sets the stage for this story about residents pulling together to rebuild salmon stocks in Quatsino Sound.

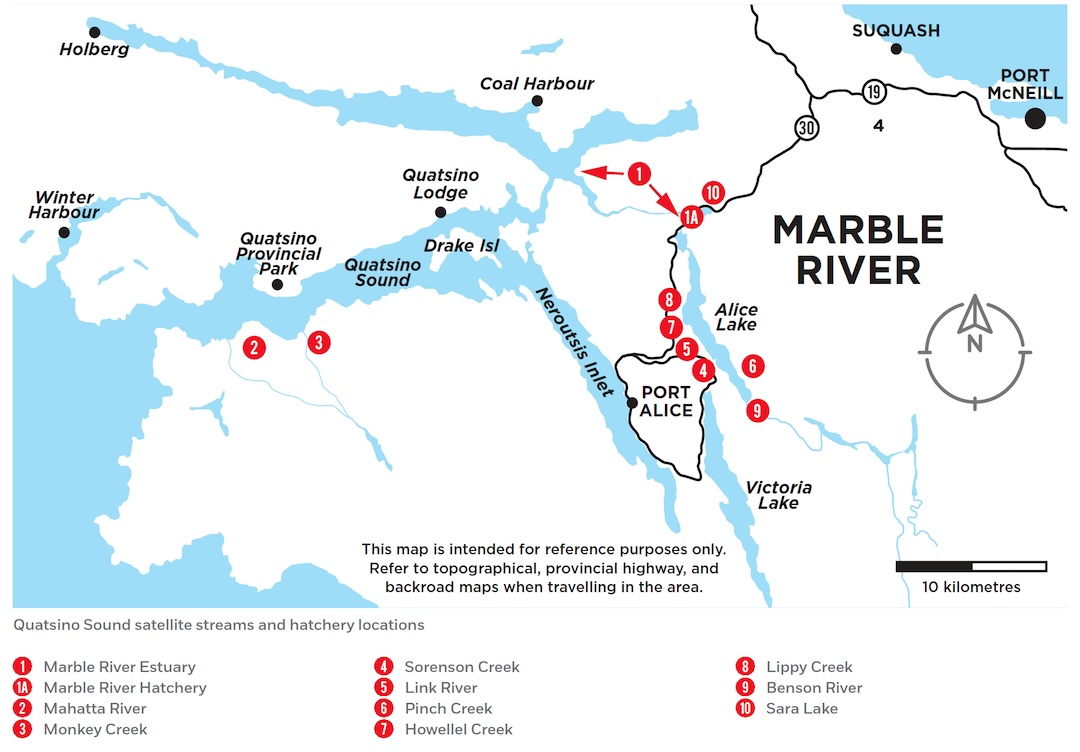

Island Fisherman magazine map

Starting Out Small: Chum Hatchery on Monkey Creek

In the early 1980s, Debbie and Grant Anderson moved to the logging camp at Mahatta River, where Grant worked as a master mechanic. Debbie had always enjoyed fishing— she could out-fish her brothers and had even taken an aquaculture course when she was in her early 20s—but salmon restoration didn’t really grab her interest until she moved to the river.

Debbie and Grant getting ready to go fishing

Monkey Creek ran behind their logging camp home. They soon noticed it contained salmon fry, which got them thinking about enhancing the creek. They reached out to Fisheries and Oceans regional community advisor George Bates, who taught them how to set up and operate a small chum hatchery on the creek.

Their activities soon expanded to include coho restoration and enhancement on the Mahatta River.

Bates retired from Fisheries and Oceans years ago, but remains involved in fishing issues as a member of the Federal Fisheries Minister’s Sport Fishing Advisory Board (SFAB) process. “Initial discussions led to an interest in hatchery operations,” he recalls. “I told them hatchery work was a 24/7 job, and that a hatchery required continuous water flow monitoring. They would have to keep it going even if something went wrong on Christmas Day.”

Bates was impressed by the Andersons’ commitment. “Volunteers never cease to amaze me with their dedication,” he says. “They come from all walks of life, each bringing their own expertise: master mechanics, fishermen, school teachers, or loggers, whom you’d think would be gruff, and yet they treated the fish like they were their babies.”

The Monkey Creek hatchery shut down when the logging camp closed, but Debbie and Grant’s interest in getting salmon back on track did not stop. After moving from Mahatta, they volunteered at the Marble River Hatchery, which is located at the outflow of Alice Lake about 7 km from tidewater.

Marble Hatchery & Friends of the Marble River Society

From that modest beginning at Monkey Creek, Debbie became the Marble Hatchery’s volunteer manager in 1997. She’s held this position ever since, while Grant has maintained his commitment to the hatchery. The hatchery is supported by The Friends of the Marble River Society. The group’s 100+ members make it the largest salmon stewardship and enhancement organization on the north end of Vancouver Island.

The hatchery began in 1981 when logger Bill Dumont wanted to rebuild Marble Chinooks to their historic 10,000-fish level. At that time there were only about 500 Chinook returning to the system. Bill realized that industrial activity, including logging and mining, was partly to blame. He felt those who benefited from competing resource demands should contribute to salmon recovery. Others agreed. Western Forest Products chipped in early by building the hatchery. Today, many of their employees remain committed to the hatchery’s programs.

According to Debbie, success is “one day not needing a hatchery.” Marble River Chinook returns have improved substantially because of these combined efforts, but work is still needed to meet Bill Dumont’s goal.

Both the mill and the copper mine are gone, negating the need for water removal from the Marble River. In fact, it has a water abundance problem, particularly during heavy rains when the river can rise 15′ in just hours.

The Marble is a Class 6 whitewater river. It’s nicknamed the “Amazon,” probably in deference to the extreme runoff that comes from its 56,000-hectare watershed. (The exact origin of the moniker actually comes from an old Marble River map with that name imprinted on it.)

Marble River Hatchery side channel

Salmon Recovery at Marble River

The Marble River Hatchery has undertaken myriad salmon recovery activities:

- It operates as a satellite rearing facility for local streams and rivers. Early on, it was apparent that coho stocks were depleted in watersheds around Alice Lake. These included the Benson and Link Rivers, Howellel, Pinch, Sorenson, and Lippy Creeks. The recovery of these systems was so successful they suspended enhancement and restoration activities after just 10 years, but the Marble and Benson Rivers still need work.

- The hatchery rears eggs for Stevens, Washlawals, and Wakwass Creeks, which are outside the Alice Lake-Marble River area.

- Extensive in-stream restoration work was done on Pinch Creek.

- In the fall, these satellite streams are monitored for escapements and general habitat condition.

- 100,000 hatchery Chinook smolts are ocean reared in a 50′ x 50′ net pen that’s maintained at Quatsino Lodge. This project increases smolt survival rate, while providing an educational experience for the public. Lodge owners Walter and Jean Schoenfelder encourage their guests to participate in salmon recovery through feeding these young salmon.

- Kids Participation Day at the hatchery introduces kids to the importance of salmon.

- Volunteers also collect data on local streams to better understand the region’s salmon producing systems. The smolt trap at Sara Lake provides species, water temperature, and water height information. Data collected here confirms coho and steelhead spawn in the lake’s tributaries.

- The Marble River rotary screw trap provides similar data, which is shared with the Nanaimo Biological Station.

- Volunteers no longer coded wire tag salmon; instead they otolith (ear bone) mark 100% of the production. Debbie says it’s like “having our own barcode on all of our salmon.”

- Otolith samples are also collected from returning brood stock and forwarded to the Nanaimo Biological Station.

- The hatchery has permits for collecting 1,000,000 Chinook and 250,000 coho eggs per year. However the high flows periodically prevented reaching those targets.

- To date (April 2022 when this article was published in Island Fisherman magazine) they had released 14,733,000 Chinook and 1,900,000 coho.

- The volunteers built a state-of-the-art side-channel to rear salmon, and they replaced a gabion wall to support the hatchery’s five 12′ circular holding tanks.

- In 2016 a major storm inflicted significant damage to the hatchery, yet it only took ten volunteers working ten days to make repairs. Fortunately, the brood stock in the net pens survived.

Marble Hatchery Gabion wall rebuild

Marble Hatchery Sara Lake trap

Debbie defines the work done by the volunteers as a community-driven operation that reverses our impacts on salmon. She adds that the Marble River hatchery owes its success to support from Western Forest Products, Friends of the Marble River, Howard Saunders, Quatsino Lodge, West Coast Helicopters, Sun Fun Divers, DH Timber, Mowi, Cermaq, the staff at the Quatse River Hatchery, Kathy Slack, Fisheries and Oceans, and the Northern Vancouver Island Salmon Enhancement Association with whom they are affiliated.

This article appeared in Island Fisherman magazine. Never miss another issue—subscribe today!

This article appeared in Island Fisherman magazine. Never miss another issue—subscribe today!

Visit the Store

$34.99

$34.99

Featured Catch

Joel Unickow halibut (Photo: Rob Frawley Lucky Strike Sportfishing Tofino)