Salmon are complex creatures. There is a misconception that weak salmon runs will recover on their own if harvesters just stop fishing, a belief that has been reinforced by the DFO’s decades-long reliance on using harvest restrictions as the number one conservation tool.

This mantra is so pervasive, that even today media reports, magazine articles, websites, blogs, and special interests who oppose salmon harvest cite “overfishing” as a top reason salmon are in their current state of decline. A cursory look at actual fishery harvest rate levels, the extent of permanently closed fishing areas, and fisheries that no longer exist clearly shows this is untrue.

Overfishing

Overfishing did occur for more than a hundred years prior to the ratification of the 1985 Canada-US Salmon Treaty. For most of that period when obscene harvest excesses often occurred, many salmon stocks exhibited remarkable resiliency against this profit-at-any-cost industrial fishing onslaught.

19th century salmon on cannery floor Vancouver Archives

To their credit, the fishing union members were amongst the first to recognize this folly.

Overfishing could only be a primary cause if the other impacts on salmon were not in play. These include urban, industrial, and agricultural encroachment on critical habitats; pollution; water extraction for competing uses; failure to enforce existing laws designed to protect critical environments; sporadic salmon recovery funding; insufficient salmon research resources; and poor hatchery practices that in some cases still exist despite demonstrated benefits from using modern hatchery protocols. As these activities accelerated, salmon’s natural resilience declined.

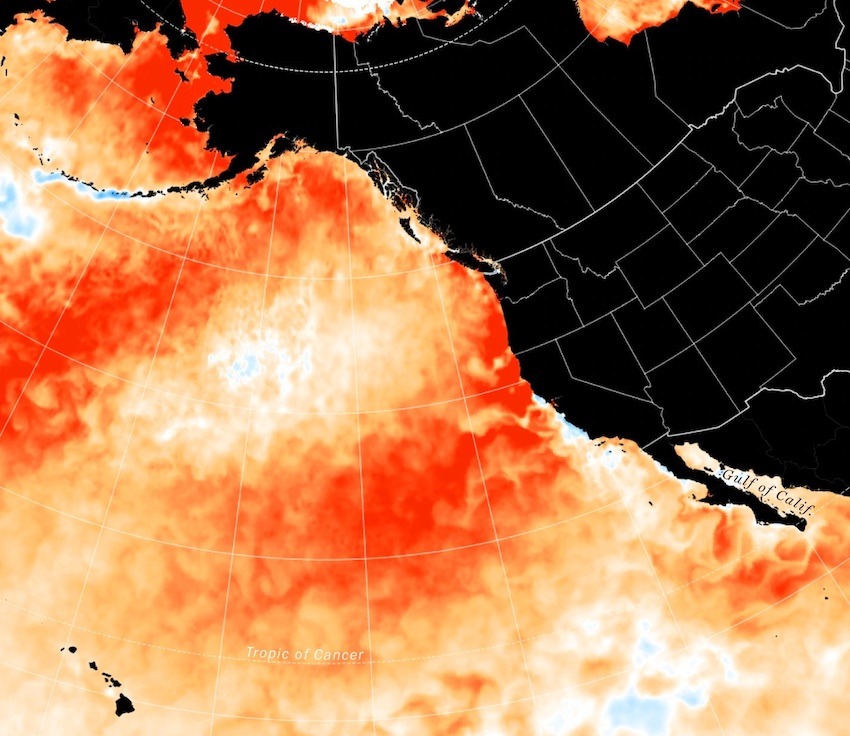

The weakest salmon runs have been forced closer to the tipping point because of more frequent, more widespread, and longer North Pacific Ocean warming events.

Ocean Warming

Graph Chart 1 The Blob 2 NOAA September 2019

Ocean warming is a long-term problem. Fortunately Canada has taken a leading role in trying to understand how these events impact far-ocean-migrating North American salmon. Credit for this initiative goes to retired Canadian scientists like Dick Beamish and Brian Riddell. A data gathering effort involving four ships and scientists from Canada, the US, Japan, and Russia recently embarked on a winter expedition to assess rearing conditions for salmon in the North Pacific. As necessary as this research is, it will not provide solutions immediately.

Fortunately, there are things that can be done right now that will help reverse the trend for endangered salmon runs. This is where protecting and restoring side channels can play a positive role in salmon recovery.

What Is a Side Channel?

We think of rivers in big-picture imagery, using words like “free flowing,” “majestic,” “mighty,” “inspiring,” and “powerful.” If salmon could talk, they would describe them as highways to and from the spawning grounds.

Salmon do spawn in big rivers, but smaller streams are the lifeblood of salmon production because they produce genetically diverse stocks and are far more numerous. Side channels are a critical spawning and rearing component of intact river ecosystems.

The “mighty” Fraser River (Nature Trust of BC)

Side Channel Definition

A side channel is a by-product of normal stream renewal and replenishment. Some changes are big. For example, the entire river flow can change its course, leaving a dry horseshoe bend that is completely separated from the main stream. Other side channels parallel the main flow. A partial blockage, like a fallen tree, is all it takes to create an adjacent channel.

Restored Side channel Charters Creek. Photo Tom Davis.

Some side channels take years to create, and some can happen overnight if the flooding event is severe enough. Side channels also occur on the smallest streams. They may only be a few meters long, but they still provide value for salmon and trout. Some side channels evolve into complex ecosystems that include bogs, ponds, and stream meanders before returning to the main watercourse.

Expansive estuaries contain highly valuable side channel habitats that are essential for salmon to acclimatize properly to salt water.

Side Channel Challenges

The only stream reaches where side channels are unlikely to develop have steep gradients and high-velocity flows over rocky terrain.

Poor side channel terrain Kennedy River Vancouver Island. Photo Tom Davis

Man-made Side Channels

Man-made structures associated with salmon enhancement activities, like spawning and rearing channels, fit the side channel definition, even though they are not created naturally.

This Nisqually River logjam will alter river hydrology (Photo: Debbie Presto, Nisqually Tribe).

Marble River Hatchery

Marble River side channel. Photo Marble River Hatchery

At the Marble River Hatchery near Port McNeill, BC, volunteers built a side channel to mimic salmon rearing under natural conditions. According to hatchery manager Debbie Anderson, the channel is used for fry rearing and holding adult brood stock.

It was excavated on swampy ground, following the natural contour of the land and retaining the original shade canopy. Runoff water and a gravity-fed supply from the Marble River keep it operational all year.

Why Are Side Channels Important and What Happened to Them?

Brian Tutty is a retired DFO habitat management biologist. When asked about side channels, he recalled this assessment from Dave Marshall, one of Brian’s Fisheries and Oceans co-workers: “10% of the habitat produces 90% of the fish … especially side channels and small streams.”

This should not be interpreted to mean 90% of a stream and the encompassing environments are not important. It simply means some areas are significantly more valuable than others.

Side channels offer additional spawning capacity. According to a 1993 review titled “Habitat Capacity for Salmon Spawning and Rearing,” in-stream spawning requirements were well understood and easy to model. However, there were significant difficulties in modeling freshwater rearing requirements for a host of reasons. In spite of this, it was clearly understood, even decades ago, that side channels provided cover from severe flooding, suffered less scour and physical disturbance, provided cool, stable summer water temperatures, and increased the overall capacity of critical habitat to sustain salmon. So if these benefits were known, what happened to all the side channels in the intervening years?

Unfortunately, side channels—because they are visibly unremarkable and physically detached from the main flow—were some of the first habitat loss casualties. This view was reinforced by Tom Rutherford, another DFO manager, who worked his way to the top of the Community Advisor ranks. “In water- sheds with any level of development, many opportunities are gone as we’ve developed some form of infrastructure where side channels used to be,” Rutherford said.

Nothing illustrates this more than stream channelization, a seemingly innocuous but devastating activity that intentionally severs side channels and other important wetland habitats from main stream flows. During serious rainfall events, this concentrates the full force of water within the primary river channel, creating potentially severe consequences for downstream lowland areas.

Rutherford also commented about the importance of securing the integrity of the upland watershed regions before embarking on downstream side channel restoration. “Watershed restoration needs to be whole watershed based. Development of green infrastructure (side channels) downstream is unwise if upstream land use is such that it threatens our investments,” he warns.

Can the Loss of Side Channel Habitat Be Reversed?

Restoring a complex side channel system at Mud Bay Creek (Photo: Dean Wong, BC Highways Ministry)

Rutherford suggests that band-aid approaches will be “ripped off pretty quickly” if weather related consequences persist. Instead, “we need to take a holistic approach to watershed health” that will protect investments made in side channel restoration.

Ian Bruce

Ian Bruce heads up the largest salmon habitat restoration umbrella group on southern Vancouver Island. He echoes the sentiment that side channels are more important for stream health and salmon recovery than ever. He singles out a lack of adequate oversight for residential development as one of today’s biggest threats to salmon.

Bruce suggests reconnecting side channels to streams and rivers where possible and sees this as a relatively inexpensive component of salmon recovery and water management. He recommends compiling an inventory of side channels that need to be protected and/or restored. Stream restoration volunteers and the public can help by identifying compromised side channel locations and reporting that information to the appropriate government agencies, or directly to organizations that undertake habitat restoration work.

The Side Channel and 2021 November Floods Connection

Are there lessons to learn from the devastating November 2021 floods?

- Are the generally accepted strategies of moving surplus water away as quickly as possible and building bigger dikes still valid, or do they just invite more severe problems down the road?

- Are solutions available that replicate a watershed’s natural sponge capacity that has been lost by forest cover removal, the proliferations of hard surfaces and permanent structures, and our reliance on storm-water infrastructure?

- Can a comprehensive side channel restoration plan play a role in minimizing water flow damage during severe weather events?

It seems these questions need to be taken seriously by the appropriate agencies before the next big atmospheric river descends on BC.

This article appeared in Island Fisherman magazine. Never miss another issue—subscribe today!

Visit the Store

$34.99

$34.99

Featured Catch

Joel Unickow halibut (Photo: Rob Frawley Lucky Strike Sportfishing Tofino)