Skeena River steelhead are a prized catch for many anglers in B.C. Photo: Chase White

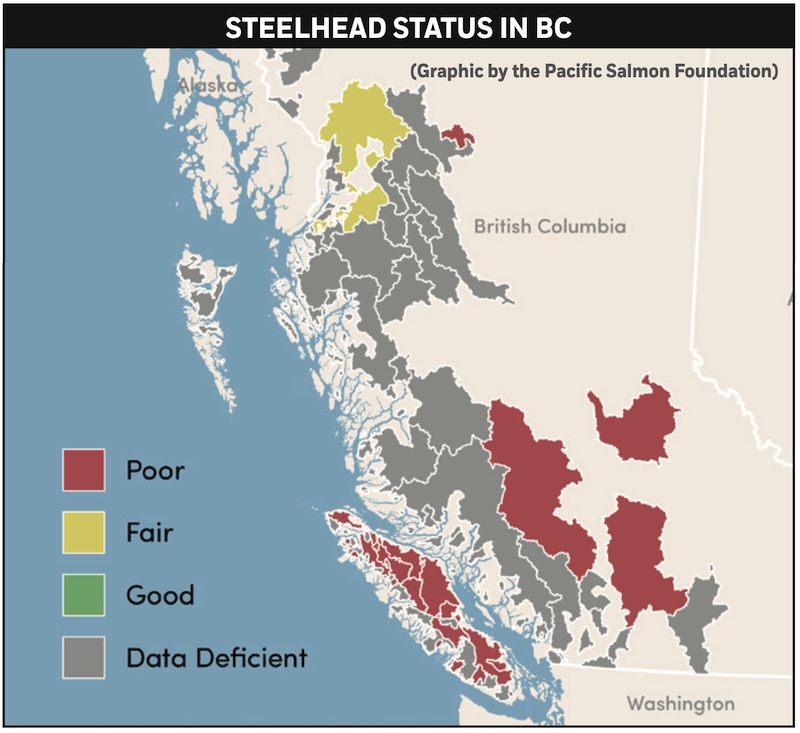

The Pacific Salmon Foundation (PSF) has compiled the most comprehensive steelhead data available to evaluate the status of this iconic species in British Columbia. While the decline of Interior Fraser steelhead is well-known, with fewer than 1,000 steelhead returning to the Chilcotin and Thompson Rivers in recent years, new assessments underscore a broader trend of steelhead declines across the province.

PSF’s 2024 report (click to download) outlines that among the steelhead population groups with sufficient data available for assessment, 86% face major conservation concerns. However, due to limited monitoring, just 19 of the 429 steelhead populations in BC have data on the number of steelhead returning to spawn in the last decade. Experts caution these data gaps could harm efforts to implement adequate conservation actions and result in silent extinctions of unique steelhead population groups.

Steelhead status in BC 2024. Graphic: PSF

The dwindling steelhead numbers are a cause of great concern for Dana Atagi, a lifelong angler and former Skeena Region Fish and Wildlife Manager for the Province of BC.

Steelhead freshwater habitats in the Skeena watershed Photo: Chase White

Steelhead freshwater habitats in the Skeena watershed – Photo: Chase White

“Steelhead are a good example of a shifting baseline. If you don’t know what used to be there, you don’t know what you’ve lost. These low steelhead numbers become normal to you,” says Atagi, who also served as Vice President, Sport Fishing Division, Freshwater Fisheries Society of BC until 2021.

“My family’s been in the fishing industry since the 1920s, and I’ve always been a steelhead fisher. But in recent years, I chose not to fish for steelhead. The steelhead fishery on the Bulkley River was open, but the numbers were just so low that I couldn’t do it. That’s never happened before. It was an ethical dilemma for me.”

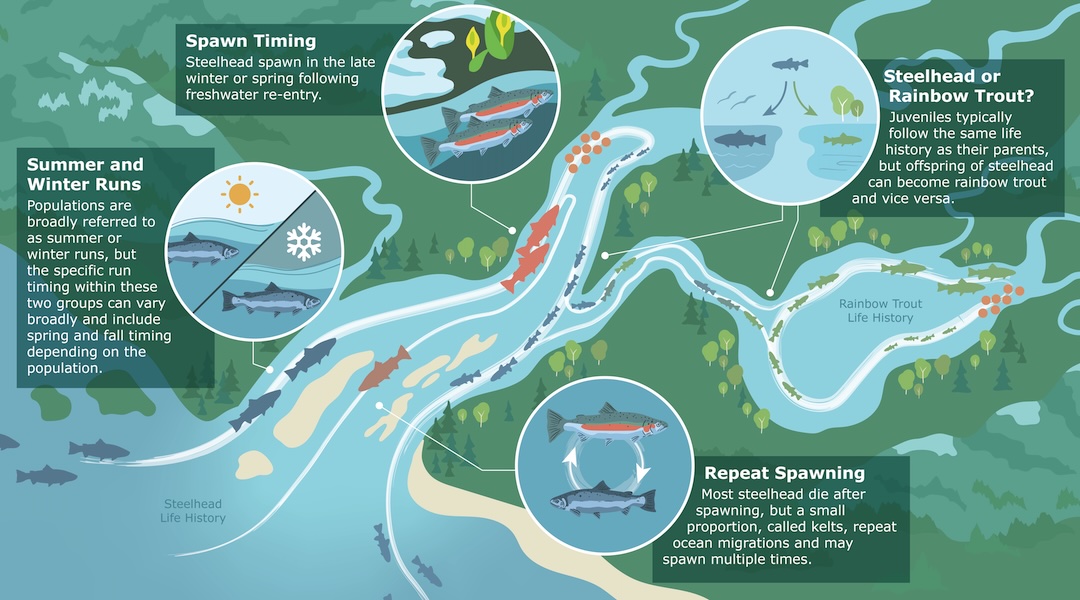

Steelhead Lifecycle vs. Management

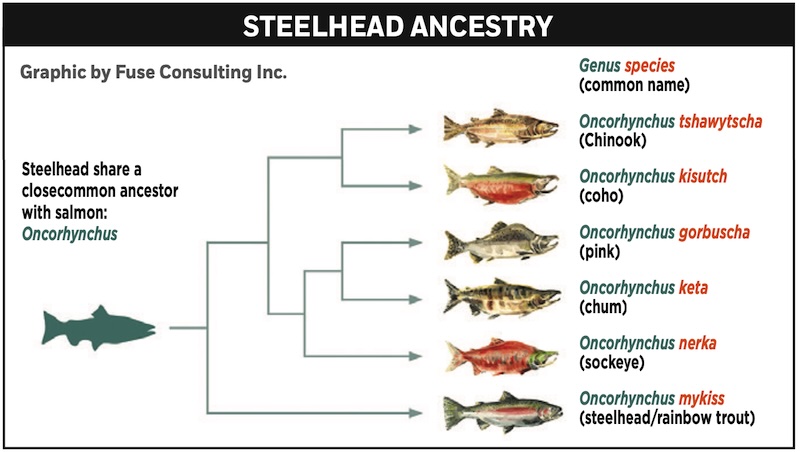

Steelhead are genetically identical to rainbow trout, but they have a different life cycle. Like Pacific salmon, they are anadromous, meaning they migrate to the ocean and return to freshwater to spawn. However, unlike salmon, some steelhead have the remarkable ability to spawn multiple times.

Steelhead Ancestry Graphic: Fuse Consulting Inc.

Atagi explains this makes steelhead management increasingly complex.

“All the things that make steelhead unique and resilient—their diverse life histories, their broad distribution across BC, their repeat spawning—also make them a challenge to manage. Their complexity makes it impossible to forecast abundance, and it’s harder to protect them, especially when their numbers are low.”

The steelhead life cycle Graphic: Fuse Consulting Inc.

Declining steelhead abundance in BC has been linked to low survival rates in the ocean, harvests in commercial fisheries, and degradation of freshwater habitats due to logging, water extraction, and other human activities. Compared to salmon, steelhead seem to respond more to changes in their freshwater habitats.

“Because steelhead spend more time in freshwater than salmon, up to 6 years in some cases, they are more sensitive to freshwater habitat pressures. Steelhead could be the canary in the coal mine for the state of these habitats,” says Katrina Connors, Director, PSF’s Salmon Watersheds Program.

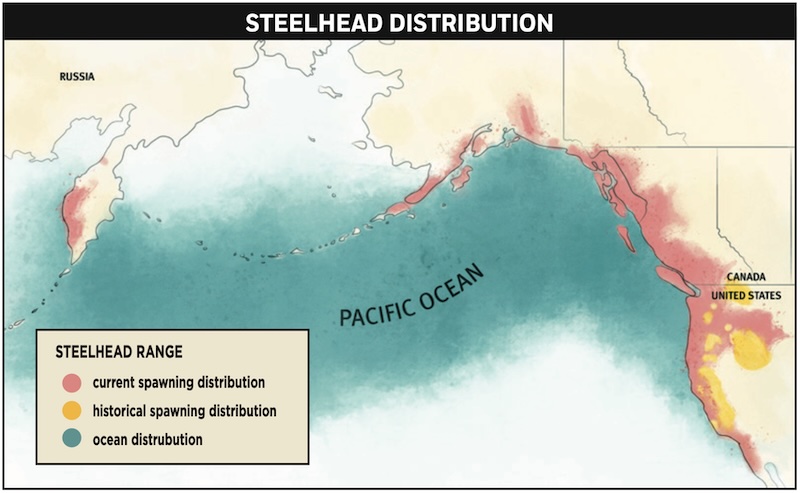

Steelhead are distributed across a vast range (Graphic by Fuse Consulting Inc.)

To help assess conservation risks, her team compiled and analyzed existing steelhead datasets and integrated this information on the Pacific Salmon Explorer, an online tool that provides free public access to comprehensive salmon and steelhead data in BC.

Pacific Salmon Explorer

Anyone can now use the Pacific Salmon Explorer to learn more about the status of steelhead across BC, identify key conservation risks in their area, or check recent abundance trends for iconic steelhead populations. View the datasets at SalmonExplorer.Ca.

PSF’s report—funded through the British Columbia Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund, a joint initiative by the Government of Canada and Province of British Columbia—calls for substantial and immediate investments in steelhead monitoring, assessment, and conservation. The report lists specific actions under four overarching recommendations:

- Maintain and expand baseline steelhead monitoring;

- Advance research to investigate key uncertainties;

- Ensure steelhead data are well-documented and broadly accessible;

- Reconfigure the steelhead management regime and implement strategies for supporting the conservation of steelhead biodiversity.

For many First Nations, steelhead are an important food source and part of their cultural and stewardship practices. Steelhead also provide essential ecosystem benefits—when they die after spawning, their carcasses release nutrients from the ocean into freshwater environments.

“Like Pacific salmon, steelhead are ecologically and culturally invaluable,” says Connors.

“It will take dedicated and sustained efforts at all levels to address the lack of monitoring and implement meaningful conservation measures to improve the outlook for steelhead in British Columbia.”

After several decades in the sport fishing sector, Atagi has a message for anglers who share his admiration for this iconic species. “Steelhead anglers need to see themselves as stewards as opposed to consumers or participants in the fishery,” says Atagi.

“If you can, show up to meetings. Advocate for the fish. It’s one of the ways you can influence decision makers and encourage them to make those hard decisions and those critical investments. Steelhead need everyone’s help—you can be part of that.”

This article appeared in Island Fisherman magazine. Never miss another issue—subscribe today!

Visit the Store

$34.99

$34.99

Featured Catch

Joel Unickow halibut (Photo: Rob Frawley Lucky Strike Sportfishing Tofino)