- Latin Name: Cetorhinus maximus

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Chondrichthyes

- Family: Cetorhinidae

Where to Find Basking Sharks and How to Identify Them

Basking sharks have been roaming through all the world’s temperate oceans since prehistoric times, when they kept company with megalodons and possibly even plesiosaurs. They are almost entirely absent from the tropics, as they prefer water temperatures between 8° and 20° Celsius (45° and 70° F). In seas that are not too hot or cold, they may be found lolling along near the surface, “basking” in the sun, wherever plankton is plentiful, particularly along thermal fronts and areas with high concentrations of chlorophyll. Although satellite tags have revealed that they can dive to well over 3,000 feet (1,000 m), and down to 5,000 feet in some cases, they seem to like hanging out near the surface and along the continental shelf, and they have been known even to enter estuaries and barge into bays.

The warmer months (from May to October) bring these languid leviathans to our Northern Pacific coastal waters. We are not really sure where they go when they leave our region in autumn, but some researchers theorize that they dive deep, cross the equator, and go to the southern hemisphere, where the warm season—and the algal bloom—is just beginning. Others believe that they move to offshore depths and go dormant or become benthic during the winter season. We do know for certain that they are highly migratory, if not very quick about it. (Their usual speed is about 2 kts.) They rarely remain in any area for more than a month or two. An individual’s home range is extensive and may span two hemispheres. Some basking sharks seen frequently in Scotland have also been recorded in Spain and Morocco. One that was tagged near the California coast traveled at least as far as Hawaii.

The scientific community needs our help to learn more about them and keep them off the extinction list. So please make a report if you see one!

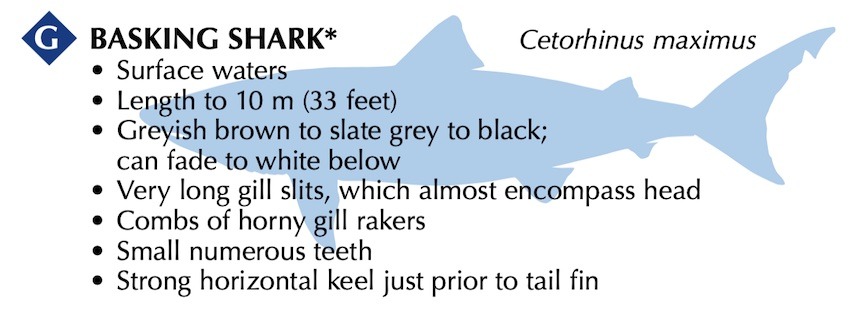

How To Recognize a Basking Shark?

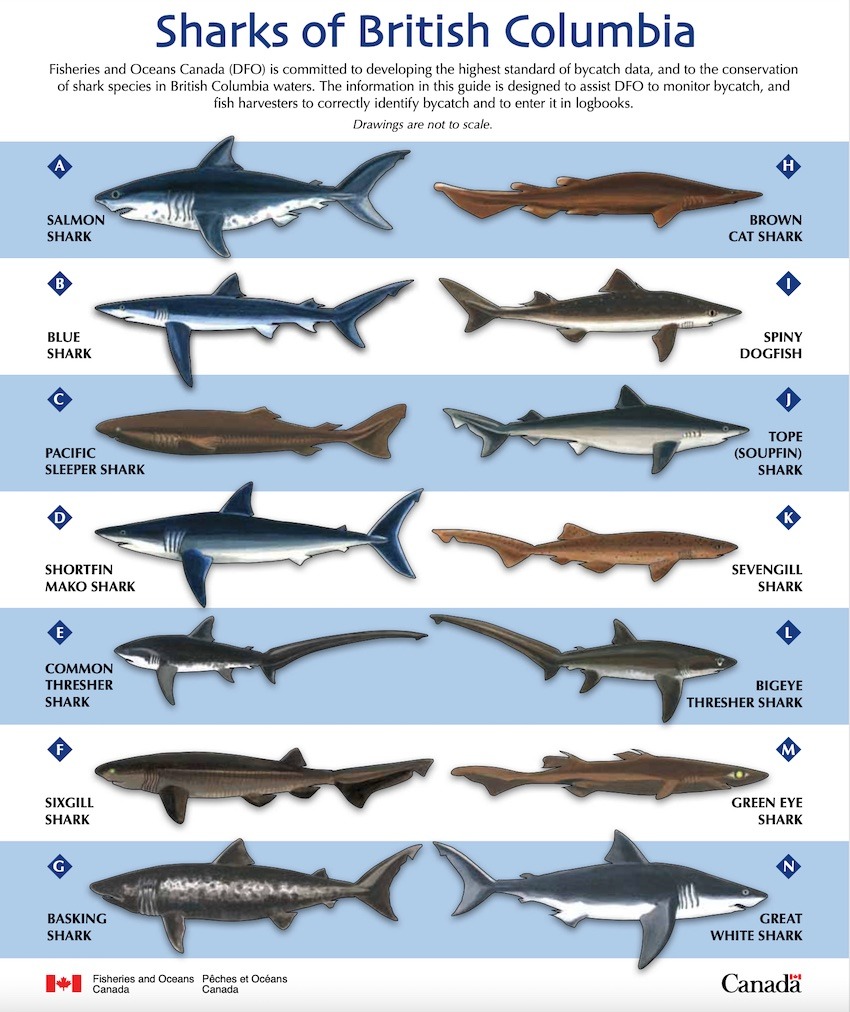

Sharks of British Columbia, Source: DFO

Download the 2 Page PDF Poster of the above here

First of all, they are big! This is the second-largest fish in the world, to be precise, coming in just behind the whale shark in the contest for enormity. An average adult is about 25′ (8 m) long—just slightly shorter than a city bus—and weighs over 10,000 lbs. The largest one on record was measured at 40.3′ after being caught in a fishing net in Nova Scotia’s Bay of Fundy back in 1851. No one was able to weigh it, but modern estimates suggest it would have tipped the scales at 45,800 lbs!

Their colours vary, but they are typically a mottled shade of dark gray or brown, occasionally bluish on top, fading to white or pale beneath. Their hides are often scarred, indicating where a lamprey latched on, or a cookie cutter shark took a chunk out of them. Many observers mistake them for great white sharks, but there are several notable differences. Basking sharks tend to have much longer, narrower bodies, smaller eyes, much smaller teeth, and gill slits that wrap nearly all the way around their heads. But the most significant and obvious distinction is the basking shark’s prodigious jaw, which can open to about a meter in diameter! They also have huge, pointed noses—which are curved or hooked in younger individuals—and impressively large, crescent-shaped tail fins.

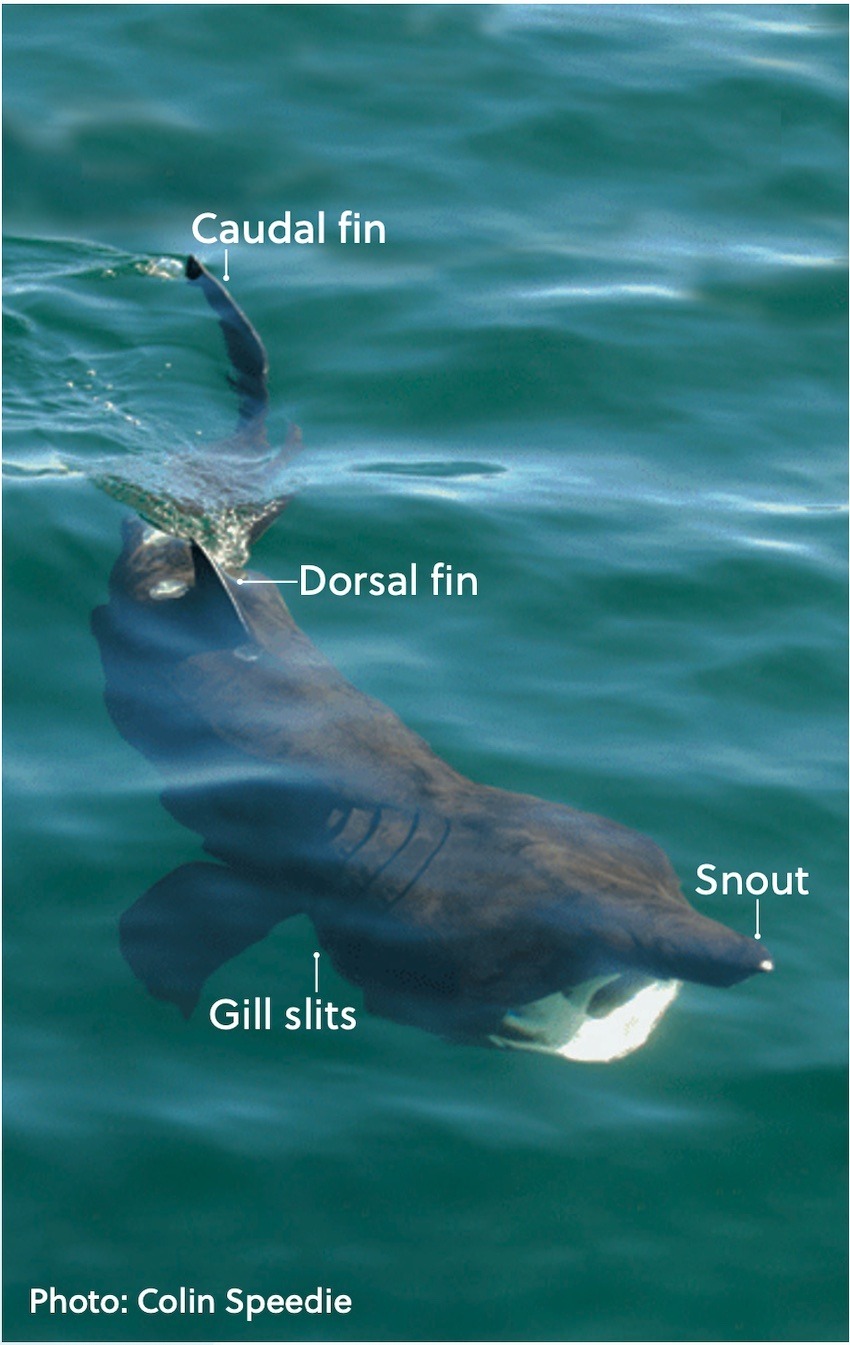

Basking Shark Photo Source: DFO Poster

Basking Shark Diet and Defense Mechanisms

This massive shark eats tiny copepods and other planktonic organisms, mostly smaller than grains of rice. Like whale sharks and megamouth sharks, the basking shark is a filter feeder, but unlike the other two, it cannot suck water through its gills. Thus, it must force plankton-rich water through its gill-rakers by dropping its jaw and swimming around looking astonished. In this manner, it filters up to 4 million pounds of water every hour!

Their skin is extremely tough, coated in a mucus layer, and covered in dermal denticles—basically each of their scales is like a tiny tooth, sharply pointed and composed of the same material. So, while the basking shark is unlikely ever to bite you, anything that bites it or tries to snuggle up to it is likely to feel it’s had a run-in with some particularly vicious and slimy sandpaper! This, along with its overwhelming size, keeps it from having any natural predators, even though it is almost totally harmless and the opposite of aggressive. On the other hand, basking shark pups are potentially vulnerable prey for other sharks, and orcas and great whites have been observed feeding on basking sharks that were already dead. Lampreys and remoras love to attach themselves to basking sharks, but basking sharks don’t share the love. When assaulted in this manner, the basking shark may hurl itself clear out of the water in order to dislodge the parasite. It is the largest shark with breaching capability, and it can do it several times in rapid succession. This purpose of this skill is not fully understood, but it might also be useful in courtship.

Basking Shark Social Behaviour and Lifecycle

Making a big splash might just help when your potential mate spends most of his or her time in a different part of the ocean. Scientists postulate that male and female basking sharks have separate lives and migration patterns, only coming together at certain times and places to breed, probably in the summertime, about every 2 to 4 years. They are so private about it, however, that no one has ever caught them in the act. It has been determined that, as with humans, fertilization is internal, and—judging by scars observed on female sharks—males likely use their hundreds of otherwise useless little teeth to hold on to their partners for dear life until the deed is done. Pregnant females probably go off alone somewhere for 1 to 3½ years until finally giving birth. Their gestation is shrouded in mystery, but it is likely the longest of any species of animal on earth, aquatic or terrestrial. Most of the basking sharks that have been captured have been females that were not pregnant at the time. For some unknown reason, only their right ovaries are functional—the left side does not make eggs.

Only one pregnant female has ever been caught and studied, and that was off the coast of Norway in 1943, so we could certainly use some new information! That female gave birth to five living pups and one that was stillborn. All of them measured between 4.5′ and 6.5′, with the average being about 6 feet (just under 2 m), leading biologists to conclude that basking sharks have the largest babies of any fish. (Great white shark pups are just slightly smaller, and whale sharks give birth to hundreds of small offspring.) They also discovered that, as in some other shark species, the fetal pups engage in oophagy, and eat up all the unfertilized eggs in their mother’s womb (which may be another function of the mysterious teeth). They emerge fully formed and ready to swim on their own. Females mature at about 20 years of age, and males quite a bit younger, between 6 and 16 years old. No one is sure how long basking sharks can live, but the best estimates suggest it is about 50 years.

Although sightings of solitary basking sharks are most common, they occasionally travel in pairs, and every few years will aggregate into very large mixed groups for short periods in summer. These gatherings of between 30 and 1,400 include both adults and juveniles, and have been reported on both coasts of the North Atlantic, between Nova Scotia and Long Island, New York, and also in the UK, between the Faroe Islands and the Isle of Man. While congregating, the basking sharks swim swim in circular patterns, breach, and feed heavily. The reasons are uncertain. Perhaps it is simply because plankton is abundant in those regions at that time. They may be drafting off of each other for more efficient feeding, as their wide-open mouths generate a tremendous amount of drag. It could also be for social and courtship purposes.

Basking Shark Photo Source: DFO Poster

Basking Shark Threats and Conservation Strategies

Once upon a time, less than 100 years ago, large numbers of these gentle giants swam the seas, and were a fairly common sight in our local waters. But for the last several decades, those numbers have been steadily dwindling, to the point that the World Conservation Union (IUCN) has categorized them as “vulnerable” worldwide, and “endangered” in the North Pacific and Northeast Atlantic. They are critically endangered in Canadian waters, and in 2010 became the first marine fish species to be listed under the Species at Risk Act (SARA).

Because they move so slowly and close to the surface, they often get hit and hurt by boats. Additionally, they are extremely easy to catch. So, for centuries, people have caught them, using their prodigious livers for oil, their skin for leather and sandpaper, and their flesh for food. Even one of their colossal fins could supply a lot of shark fin soup. Overfishing has been a problem for them all over the world, especially in Asia.

Climate change threatens their habitat by raising ocean temperatures and contracting the temperate zones in which they range. Further, the ocean’s absorption of atmospheric carbon dioxide is causing the sea to become gradually more acidic and less hospitable to many of the forms of zooplankton that comprise the basking shark diet.

But the sad story of their decline contains one particularly painful chapter. Here in Canada, back in the 1940s and 50s, commercial salmon fishers found them hard not to catch, and the passive plankton-eaters were so big that they often broke the gill nets. So between 1955 and 1969, the DFO directed an “eradication program” for these “destructive pests.” Fishing crews were encouraged to hunt and kill them, and a federal fisheries patrol vessel had a ram with a sharp blade mounted to its bow, designed to slice basking sharks in half. This clever innovation was lauded in the mid-50s by the Victoria Times and Popular Mechanics. During its first year it destroyed 105 basking sharks, and over the course of its tenure it slaughtered 413. Consequently, the Canadian basking shark population dropped by about 90%.

Now we need to right past wrongs and make up for lost time. Basking sharks are now protected in most countries, and international trade agreements make it illegal to sell their body parts, although a black market still exists in many places. Here in Canada, the DFO implemented a Shark Sightings Network in 2007, so that marine communities can keep their “eyes on the water” and improve our collective understanding. In the USA, NOAA has a similar program. If you see one, please slow down to no more than 6 kts, don’t make any sudden changes in direction, consider shifting to neutral if you are within 100 m, and make a report using one of the methods at the end of this article.

Basking Shark Trivia

Relative to their overall size, they have the smallest brains of any shark, which may come as no surprise given their slow, passive way of life. Their livers, however, are among the largest in the animal kingdom, extending most of their body length and accounting for a quarter of their overall weight. High levels of squalene—a low-density hydrocarbon—in their livers give them virtually neutral buoyancy. In the early 20th century, their liver oil was used in making lubricants, lamp oil, cosmetics, and even perfumes.

They can shed and regrow their gill rakers, which is a 5-month process.

Lampreys often attach themselves near the location of a male shark’s reproductive organs, called claspers, which makes it much harder for biologists to identify the sex of the shark.

The basking shark is the last living species in its taxonomic family, Cetorhinidae. The family name is comprised of cet-, meaning “whale or sea creature,” and rhinus, meaning “prominent nose.” The species name, maximus, is pretty easy to decipher. So there you have it—a whale of a big-nosed, really huge sea-creature.

Basking Shark Photo Source: DFO Poster

Throughout history, people have seen them and fled in terror, unaware that there is nothing to fear. Groups of basking sharks cruising along in single file have sparked tales of sea serpent sightings. And when their enormous carcasses with their relatively small skulls have been washed onshore or hauled up in fishing gear, people thought they were the remains of mythic sea monsters. In 1977, a basking shark body found by Japanese fishermen was initially believed to be that of a plesiosaur!

With its doorway-width jaw, could a basking shark have been the biblical Jonah’s “whale?” Nope. The unfortunate prophet might have fit most of the way into the shark’s mouth, but its esophagus is only a few inches in diameter.

Strangely enough, one of these benign behemoths accidentally caused the only shark fatality in the history of the UK. In 1937, off the coast of Kintyre, Scotland, a boat was capsized by a breaching basking shark, causing three of the occupants to drown. So if you see one while out boating, take photos and videos, but be sure to give it plenty of space—unless you’re in the mood for a swim in the salt-chuck!

Please help spread the word!

How To Report Shark Sightings:

- By phone toll-free: 1-877-50-SHARK (1-877-507-4275)

- By email: [email protected]

- By filling out an online Shark Sightings Form, available at: https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/sharks/report-eng.html

- DFO has also developed new Basking Shark outreach materials:

The poster and brochure (PDF versions) can be downloaded from: Pacific marine mammals and sharks | Pacific Region | Fisheries and Oceans Canada (dfo-mpo.gc.ca).

In the USA: Please report any sightings including the date, time, and location, as well as any comments to 1- (858)-546-7023 or send an email to [email protected].

Visit the Store

$34.99

$34.99

Featured Catch

Joel Unickow halibut (Photo: Rob Frawley Lucky Strike Sportfishing Tofino)