THE ANSWER: Everything, and here’s why.

Federal Fisheries (DFO) is one of the most contentious portfolios for politicians to handle. Coincidentally, when this article was under development the Prime Minister appointed Vancouver Quadra MP, Joyce Murray, as the sixth Minister of Fisheries in the last six years. The job is notorious for high Ministerial turnover. This is not an indication of prior successes. Fishery issues can degenerate into a toxic stew of rights, assumed rights, conflicting agendas, mistrust of government, harvest allocation fights, public interest concerns, complex regulation and enforcement, and competing resource interests too often mixed with departmental dysfunction and politically expedient decisions. Environmental groups have recently discovered this is fertile ground for activism, while Supreme Court determined First Nation rights override everything.

These complexities have confused the public about fisheries, and created uncertainty for those whose livelihoods depend on fishing. Just whom can you believe? Are killer whales going extinct? Are we down to our last Chinook salmon? What does selective fishing really mean? Should we get rid of hatcheries? Does it matter where salmon migrate in the ocean? Can we still fish? Can I provide for my family?

This article tries to answer these questions and explain how key issues interconnect.

Killer Whales

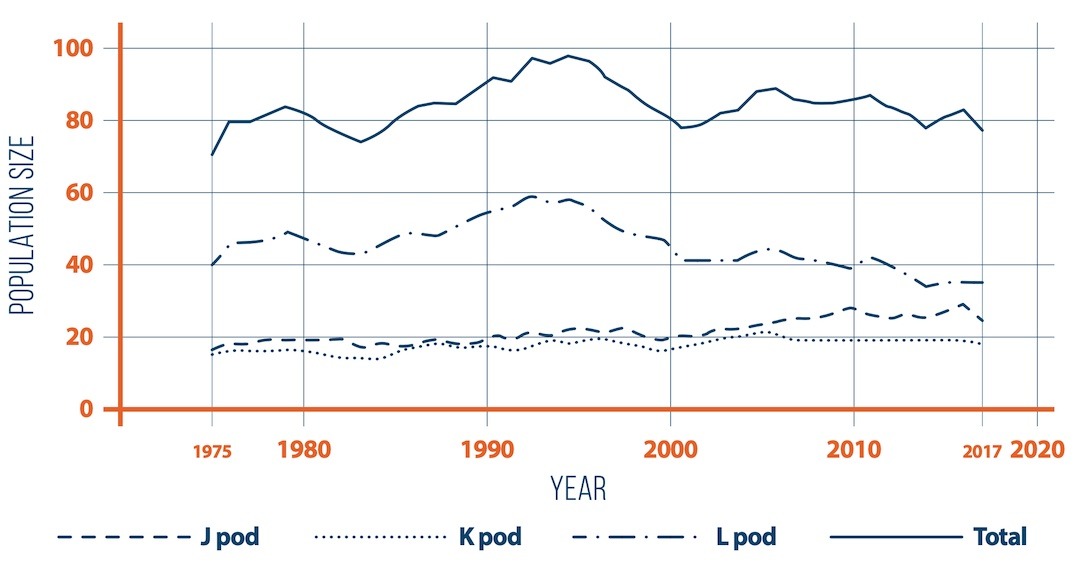

Let’s start with killer whales, specifically salmon-eating Southern Resident Killer Whales (SRKW). There are three pods (J, K, and L) in the SRKW group totaling 73 animals.

Population trend for SRKWs by Pod 1975-2017. Data Source: DFO

SRKW’s are the struggling cousins of all killer whale clans that inhabit the eastern Pacific Ocean between California and the Bering Sea. Oddly the status of other groups of fish- eating orcas is improving. For example the Northern Resident Killer Whale population has doubled to over 300 since the 1970s, while the SKRW population is stuck in neutral. Transient mammal-eating killer whales are also prospering, while Humpback and Grey whales are on the rise and seals and sea lions are abundant. So what is wrong with the SRKWs?

Some of the answers come from a Fisheries and Oceans February 15, 2018 Discussion Paper, titled “Proposed Salmon Fishery Management Measures to Support Salmon Prey Availability for SRKWs.”

Important Background Bullets From That Discussion Paper:

- Focus recovery efforts on prey availability and increasing prey abundance.

- Identify & implement fishery management measures.

- Reduce physical and acoustic disturbance.

- SRKW diets are 90% mature Chinook & some Coho during spring and summer months, shifting to mature Chum salmon in the fall.

- Their winter diet includes non-salmon species.

- Little research on winter feeding habits exists.

- Chinook marine survival rates have declined in 4 of 5 key conservation units SRKWs relied upon by (Riddell, 2013).

- Fraser and Thompson River stream-type Chinook account for the bulk of the decline in Chinook conservation units.

Quotes From The Document Providing Background Context:

- In reference to Fraser-Thompson stream-type Chinook: “These populations exhibit an offshore migration pattern.”

- Conversely: “Fraser summer ocean-type Chinook have been abundant for over a decade and have a far north distribution.”

- Previous Chinook management measures “substantially reduced exploitation rates over the last 10 years, well below historic sustainable levels, [yet] there has not been a rapid recovery of many Chinook populations, suggesting other factors are also contributing to ongoing low productivity.”

- “While it seems likely that there are large, scale processes influencing Chinook salmon productivity, no single factor can be readily identified at this time to account for the recent patterns or trends observed for southern BC Chinook.”

- In 2011 and 2012 an international panel of scientists convened to review existing data on SRKWs.

The report noted that “reduction in coast-wide harvest of Chinook may not necessarily translate into greater availability of Chinook for SRKWs due to a range of factors.” - The SRKWs have a low percentage of breeding-age females.

The Discussion Paper Listed Other Action Options For Consideration

- Apply management measures to other fisheries.

- Enhance and restore habitat.

- Consider producing more Chinook: “Current hatchery production increases may be beneficial to SRKWs.”

- Manage other predation sources (seals & sea lions).

- Increase Chinook forage by adjusting harvest of Chinook prey species (herring).

To my knowledge only minimal increased hatchery production has been acted upon specifically for SRKW recovery.

We are heading into the fifth year of targeted SRKW measures, which include geographically large fishing closures, to stabilize SRKW prey availability and reduce encounters with marine traffic. However the SRKW population decline has continued, dropping from 76 to 73 animals.

Unprecedented Chinook non-retention restrictions were introduced in 2019. These continue to impact most major public fisheries on the BC south coast, lasting from April 1 to July 31 or longer in some cases. Commercial and First Nation Chinook harvesting was also significantly restricted.

Regardless of unprecedented low Chinook harvest rates compared to previous decades there has been a steady drumbeat, mainly from environmental groups, to further limit or eliminate marine Chinook fisheries.

In October 2021, Raincoast Conservation, supported by the David Suzuki Foundation, World Wildlife Fund, Georgia Strait Alliance, and the National Resources Defense Council, proposed ending “directed Chinook fisheries in marine waters” and “to close to the full extent key Chinook foraging areas to all salmon fishing from March 1 to December 1.

Fishery closures have been DFO’s “go to” salmon recovery tool for decades. With rare exceptions it either hasn’t worked, or has only worked for a short time; otherwise struggling Chinook runs wouldn’t be in their current condition.

Chinook Ocean Migration Patterns Matter

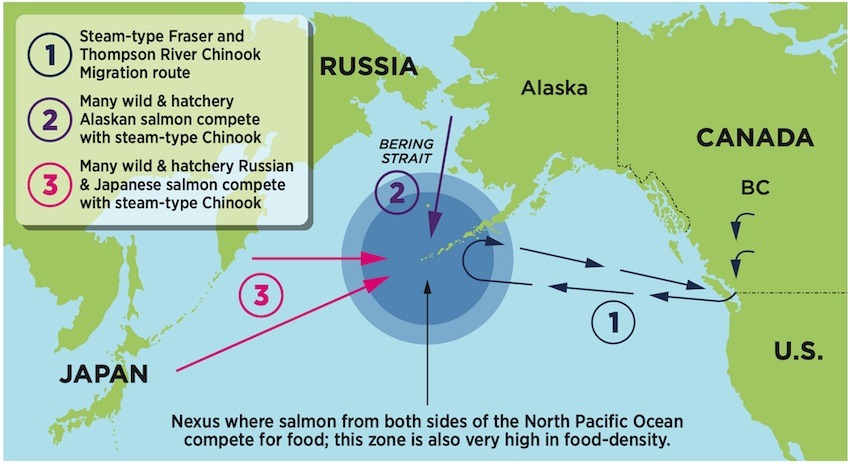

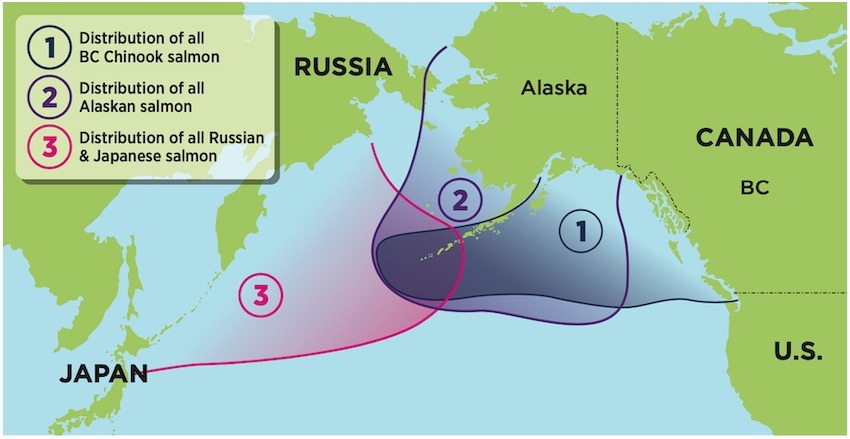

The 2018 Discussion Paper identified a significant problem. Weak runs of Fraser and Thompson stream-type Chinook, an important SRKW food source, are all far-migrating ocean stocks.

Ocean distribution for Fraser/Thompson stream-type Chinook. IFM Image

These North Pacific feeding grounds support wild and hatchery runs of salmon from western North America including Alaska, as well as Russia and Japan. Many BC Chum, Sockeye, Pink, and Steelhead runs also migrate to this region.

Pacific Ocean salmon distribution. IFM Image

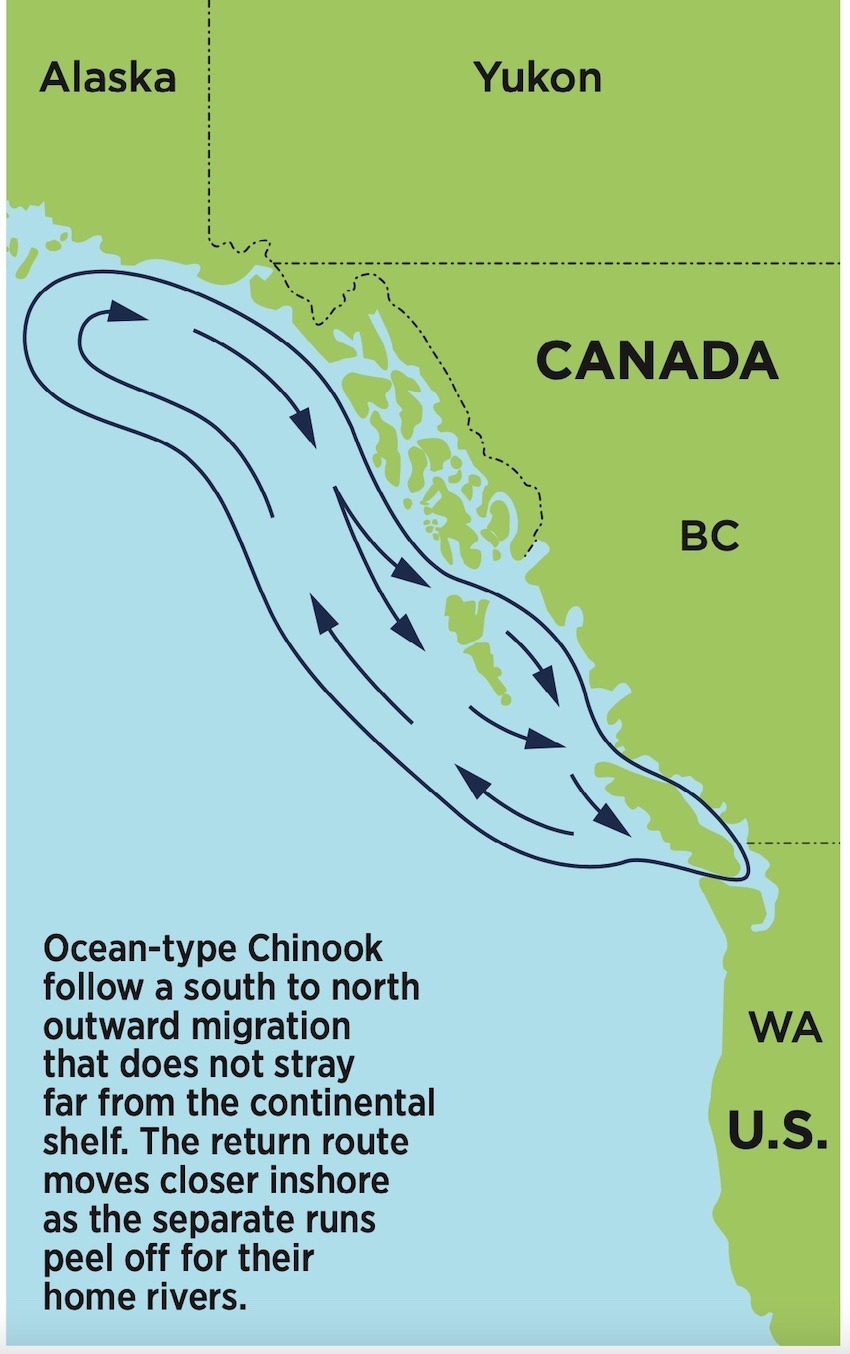

Distribution for BC ocean–type Chinook salmon. IFM Image

In the 1990s, Dr. Dick Beamish, an internationally recognized DFO scientist, identified that a regime shift, characterized by warming ocean conditions, was occurring in the North Pacific. Warm water leads to reduced quality and quantity of salmon forage, while bringing with it new predatory fish species. Regime shifts are impactful long-term oceanographic events, unlike short duration El Nino events.

The second factor affecting BC’s stream-type Chinook is the massive Pink and Chum salmon production coming from Japan, Russia, and Alaska. These juvenile salmon are believed to create too much competition for a diminishing food supply. It is just coincidence that many struggling BC salmon runs have this far ocean migration trait in common?

The Discussion Paper also notes that Fraser River four-year-old summer Chinook have been returning at abundant levels for the last decade, and that they are northward near-coastal migrating stocks. This indicates there is variability in survival and productivity within the Fraser/Thompson system and that one of the factors that accounts for this is ocean distribution. Ocean-type Chinook also migrate to sea shortly after emerging from the gravel as fry, and generally return to their home streams later in the year, hence the term “fall run.”

It is also important to note that other key Chinook stocks have been outperforming weak runs. According to the Pacific Salmon Foundation 2018 State of Pacific Salmon document, Central Coast Chinook returns are at 16% above the long-term average.

Ocean-type wild and hatchery Georgia Strait and west coast Vancouver Island hatchery Chinook have also bucked the downward trend.

Georgia Strait Chinook were the albatross around Canada’s neck during the early Canada/US Salmon Treaty years. However in the last decade, according to DFO data, they have rebounded significantly.

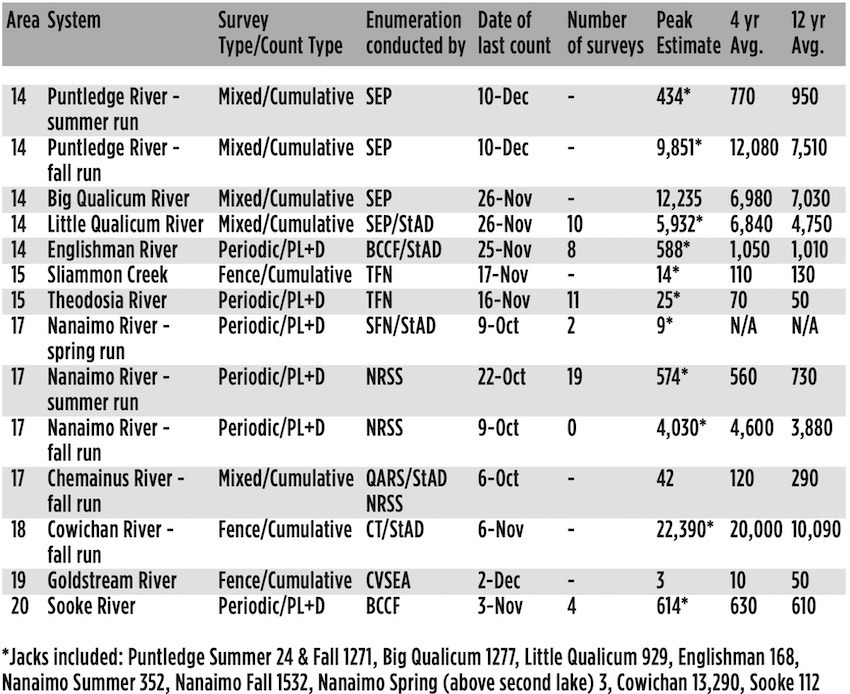

Chinook escapement counts to date for 2020 trait of Georgia salmon surveys. Counts include adults and jacks combined as well as brood removals. When available, jack totals are provided below the table. Average are total return to river.

The 2020 escapements were almost double the 12 year average and well above the recent 4 year average.

Rebuilding Georgia Strait Chinooks included substantial volunteer restoration efforts, hatchery augmentation for production and stock rebuilding purposes, and sensible harvest reductions that did not cripple recreational fisheries. This recovery model was not used for depressed Fraser River stocks. Instead hatcheries were closed, new hatchery proposals were shelved and minimal recovery investments were made.

Another key factor that separates stream-type from later returning Chinook runs is these Chinook spend at least one extra year in freshwater. This means they are susceptible to higher freshwater mortalities from predation, climate change, natural disasters and human caused impacts. They also have much longer juvenile and adult in-river migrations exposing them to added risks.

Currently, many BC salmon stocks are underperforming including important Chinook runs. Yet key Chinook stocks are also bucking the trend, indicating that a rebuilding road map exists without throwing important fisheries under the bus.

The UBC SKRW Prey Availability Study

Dr. Mei Sato with the acoustic gear

The team expected to find greater Chinook availability in Johnstone Strait because the NRKWs’ physical condition was more robust than their SRKW cousins, who were thought to be malnourished and in some cases starving. What they found surprised them. Chinook prey availability in Juan de Fuca Strait was 4 to 6 times higher.

This study was not intended to measure total abundance, nor was it intended

to revisit well ploughed ground, like assessing the importance of Chinook to SRKWs, or determining which stocks contributed most significantly. The goal, using multi-frequency echo sounders, was to determine the relative abundance of Chinook in each group’s primary summer feeding habitats. The data concluded that there was adequate abundance of Chinook for SRKWs in Juan de Fuca during the summer feeding period.

Andrew Trites

Professor, Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries

Associate Member, Department of Zoology

Director, Marine Mammal Research Unit

So, were these results greeted positively? Within a matter of days the criticism started. In fact, during a CTV News interview on the subject, Dr. Trites commented that “there shouldn’t be mudslinging,” adding that “science is not about beliefs; it’s about testing, and that’s what we did.” What’s confusing is that the vitriolic reaction came from the Orca Behavior Institute. This organization is a non-profit SRKW advocacy group based in Friday Harbor, WA.

The study’s authors also noted this problem. “There is little data to test the hypothesis” suggesting a lack of forage in the SRKW summer feeding grounds. Consequently the UBC results ran contrary to this much hyped, commonly held—but apparently poorly researched—belief.

However, according to Trites, the study did not dismiss the lack-of-prey theory, as his critics suggested. He pointed out that prey shortages may exist in other locations and at other times of year—which should prompt more peer-reviewed research. They simply reported that Chinook shortages were not apparent in this key summer feeding area.

Peer-reviewed, science-based messaging is critical for problem solving. The starvation story has been used as a cudgel by activist groups calling for the elimination of marine Chinook fisheries. To date, this anti-fishing rhetoric has been largely successful in confusing the public about fishery impacts which, as reported in the 2018 Discussion Paper, were already well below historic levels before much harsher restrictions were implemented in 2019.

Disclaimer: In 2018, the author volunteered for a day with the UBC Juan de Fuca research group.

Visit the Store

$34.99

$34.99

Featured Catch

Joel Unickow halibut (Photo: Rob Frawley Lucky Strike Sportfishing Tofino)