I believe that the caddisfly hatch offers more exciting dry fly fishing than any other hatch. In this article on trout foods and the patterns that imitate them, we will delve into the lifecycle of the caddisfly, or “sedge”, as we Canadians often call them.

Caddisflies undergo complete metamorphosis just like midges do; there is a larva, a pupa, and an adult stage. We’ll begin in very early spring, when the eggs are still lying on the river or lake bottom.

As winter closes and spring arrives, the ice comes off the lakes and slower streams, waters start to warm, and the caddisfly eggs hatch into larvae. There are two distinct types of caddisflies, and therefore two distinct larvae. One is a web-spinning caddisfly and the other is a case-building caddisfly.

Web-Spinning Caddis Larva

The web-spinning larva is a free-swimming insect that wriggles and bounces around on the bottom looking for food and trying to avoid getting eaten. These larvae have no cases. When it comes time for them to pupate, they find a crevice in a rock and spin a web, much like a spider’s web, over themselves to seal themselves into their cocoon. They then undergo metamorphosis and emerge a few days later as a pupa. Trout readily feed on the web-spinning larva, and imitating it with a good fly pattern is easy and effective.

Web Spinning Caddis

Tying Steps

- Tie on the thread; tie in the black monocord for the rib.

- Form a dubbing loop or tie in the wool, then wrap the material forward over 2⁄3 of the hook shank. Tie off and trim the excess.

- Form a dubbing loop or tie in the brown wool or seal. Wrap forward to the head. Tie off and trim excess.

- Tie in a short length of white calf tail perpendicular to the hook shank. X it in. Tie it off and trim the excess.

- 5. Whip finish the head and cement.

The case-building caddis hatches from the egg and crawls along the bottom collecting tiny sticks, branches, and gravel, and glues this material around its abdomen and thorax to make a case. It looks much like a tiny hermit crab. Once the case is built, the insect carries on crawling and feeding. When the time comes for this larva to pupate, it draws itself into the case and seals the top. It then undergoes metamorphosis and emerges as the pupa.

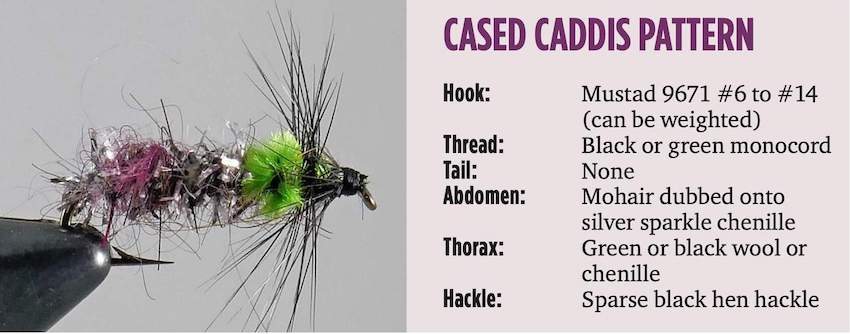

Cased Caddis Pattern

Trout feed on these cased caddis larvae just as readily as they do the web-spinning larvae. If you catch an early spring trout, especially in a river or stream, you can usually feel and hear the gravel in its stomach from the cases if you cradle it in your hand. A great imitation of the cased caddis is described in the image below.

Cased Caddis Pattern

Tying Steps

- Tie on the thread and wrap to the butt of the hook. Tie in the lead if you plan to weight the fly.

- Tie in the silver chenille.

- Dub the strands of mohair onto the chenille. Wrap the chenille forward 2⁄3 of the way up the shank. Tie off and trim excess.

- Tie in the green chenille. Wrap to the head. Tie off and trim excess.

- Tie in, at the tip, one black hen hackle. Wrap 2 or 3 turns. Tie off and trim excess.

- Whip finish the head and cement.

The key to effectively fishing either of the caddis larvae is to ensure you get the fly on the bottom. Fishing a caddis larva seems to be more effective in moving water than in lakes, and a dead drift presentation right along the bottom works best.

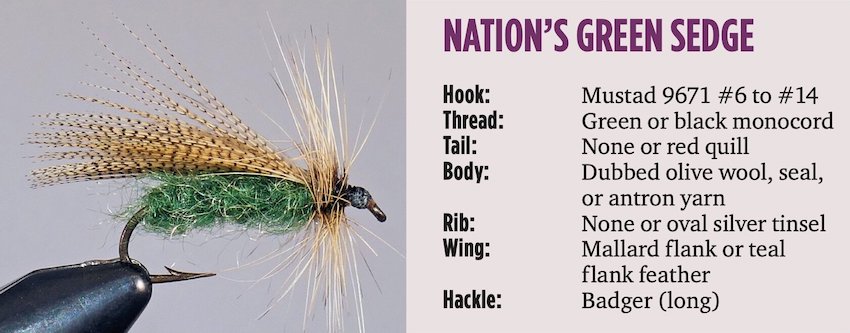

Nation’s Green Sedge

Whether it is a web-spinning or case-building species of caddisfly, the pupae look basically the same when they emerge from their transformation. They have long abdomens, with their wings, ends that the pupae use like oars to swim quickly to the surface after they emerge from their cocoons on the bottom. Old Bill Nation designed an excellent fly pattern to imitate the pupae. It is known as Nation’s Green Sedge, and it works as well today as in yesteryear. Below is how you tie it.

Nation’s Green Sedge

Tying Steps

- Tie in the thread and wrap to the butt.

- Tie in the tinsel (if you want a rib).

- Form a dubbing loop and dub on the olive body material. Wrap forward to the head forming a fairly fat body. Tie off and trim excess.

- Wrap tinsel forward to form the ribbing. Tie off and trim excess.

- Tie in the mallard flank overwing about 11⁄2 times as long as the hook shank. Tie off and trim excess.

- Tie in one long fibre badger hackle. Wrap 2-3 times and tie off. Trim excess.

- Whip finish the head and cement.

Once the pupa cuts its way out of the cocoon, it immediately heads for the surface using its swimmerets to propel itself. The swimmerets pump like little oars and give the insect a very distinctive fast, pumping motion. To fish your imitation effectively in lakes, you must get the fly down deep using a fast-sink or extra fast-sink line and retrieve the fly using quick, short strips. In rivers you can use short down and across casts, allow the fly to sink a bit, and then use the drag of the current to draw the fly to the surface naturally. In either case, hang onto your rod because the trout usually hit the rising pupa hard.

When the pupa reaches the surface it immediately cuts its way out of the pupal shuck and emerges as the adult sedge. They look like moths at first, but you can distinguish them from moths and other insects by the way they hold their wings folded tent-like back over their abdomens. The adults flutter, run, and bounce around on the surface of the water until their wings are dry enough to keep them airborne, and then they fly off into the bushes to mate. Once that business is done, the females return to the water’s surface to lay their eggs. The running and fluttering activity on the surface attracts just about every trout in the water, especially at dusk. The rise to the running caddisflies is violent and unnerving. The trout may slash or jump out of the water and land on top of the insect to slow it down by drowning it. Then the fish will immediately return and eat the morsel. Keep this in mind when fishing the dry caddis hatch. You should learn to hesitate before setting the hook to see if your fly has actually been mouthed, or if the fish simply slapped it and left it. If the latter is the case stay prepared because the trout will be back in a split second to take the fly.

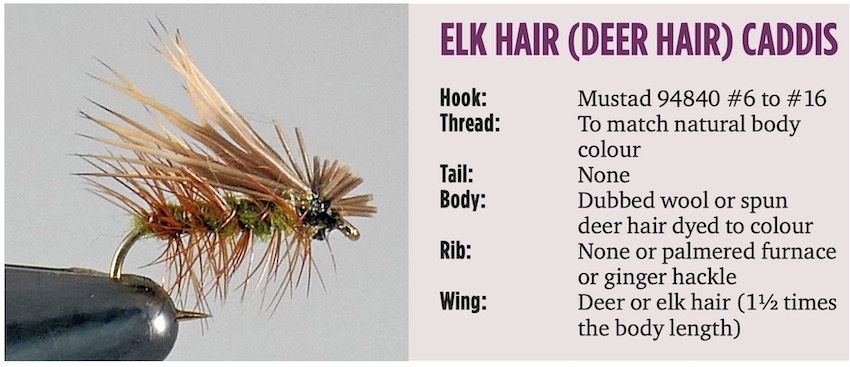

Below is the elk hair caddis (or deer hair caddis), which is still one of the best imitations of the adult caddisfly. I often tie this pattern with a clipped body of spun deer hair instead of the antron or wool standard. Clipped bodies float a lot better than dubbed ones, and a spun deer hair body is much more durable than a tied-down deer hair body such as that of the Tom Thumb (another pattern that is used extensively to imitate the dry caddis). Other patterns that work very well as adult caddisfly imitations are the Mikulak Sedge and the Goddard Caddis.

Elk Hair (Deer Hair) Caddis

Elk (Deer) Hair Caddis

Tying Steps

- Tie in thread. Wrap to butt. Tie in hackle.

- Form a dubbing loop. Dub on the body material and wrap forward to the head, forming fairly fat body. Tie off and trim excess.

- Palmer the hackle forward over the body. Tie off and trim excess.

- Tie in the deer hair wing. Avoid flaring it too much. The wing should lie tent-like over the back of the fly. Tie off and trim excess.

- Whip finish and cement the head.

Fishing caddisflies is easy, especially the adult stage. In a good hatch, when the rise is strong, almost any fly on the surface will be eaten, yet I have seen situations during a light hatch when the exact size, shape, colour, and motion were necessary to convince a fish to strike. Matching the hatch as best you can often pays big dividends when fishing the caddis hatch, both when fishing the pupa and the dry adult.

Do yourself a big favour and pay close attention to details when tying up or buying flies to match the natural insects in all their life stages, but pay particular attention to the pupa. I have seen innumerable refusals of pupa imitations that just weren’t quite right. Yet I have changed flies and cast out again to the same cruising fish only to have it slam into the fly with no hesitation, when the only difference between the refused pattern and the one taken was a slight colour variation in the thorax.

Keep a small assortment of caddis pupae and dries in your boxes at all times. The naturals are around from early spring through fall. The major hatches occur in late May through early July, depending upon where you fish, but a few pop up all summer long, and the trout will often recognise them and eat them opportunistically. When all else fails, tying on a caddis pupa and trolling it around a lake or sweeping through a good run in a stream can often result in a fish or two. Give it a try.

This article appeared in Island Fisherman Magazine. Never miss another issue—subscribe today!

Visit the Store

$34.99

$34.99

Featured Catch

Joel Unickow halibut (Photo: Rob Frawley Lucky Strike Sportfishing Tofino)