Seal & Sea Lion Populations

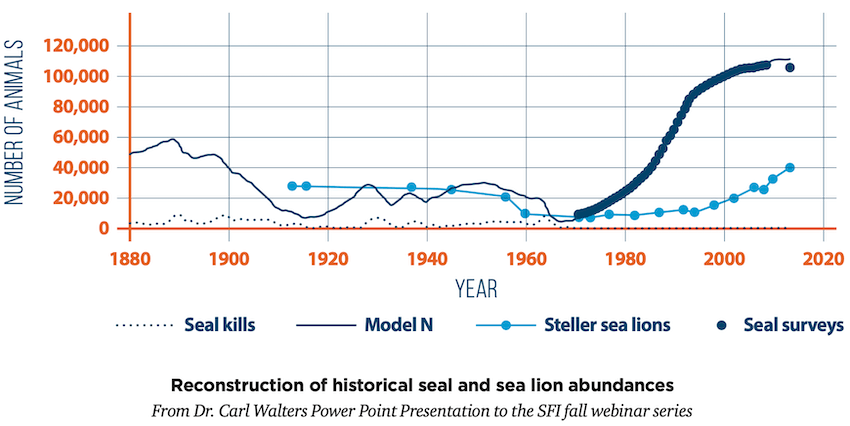

Most of us have grown up in a world where seal and sea lion hunts have not only been banned but roundly criticized. Yet few realize that a half century of protection of these animals has resulted in major population increases, with the only counter-balance coming from natural predators like transient killer whales and sharks.

Over the same time period, we have become increasingly enamored with them, to the extent that protecting seals and sea lions forever seems to have replaced the original goals of halting their population declines and putting them on the road to recovery.

White Harbour Seal

It’s difficult not to love a cute face with big brown eyes. However it’s also difficult not to love a deer or admire a Canada goose. That is until deer ravage suburban flower beds and geese leave so many droppings in public parks that residents demand action against both. Start a discussion about harvesting seals, however, and you risk getting some serious blowback. Thank the images from the east coast harp seal pup kills for that reaction. The problem is, this urban perception ignores a west coast cultural reality along with a basic understanding of predator/prey relationships.

Harbour Seals in Oak Bay Marina

Harbor seal eats a fish Nanaimo BC

First Nations

First Nations living along the Pacific coast harvested seals and sea lions for thousands of years. These hunts provided clothing, food, materials for tools and weapons, and highly sought-after oil for personal and trade uses. The hunts were culturally significant and sometimes necessary for getting through tough times.

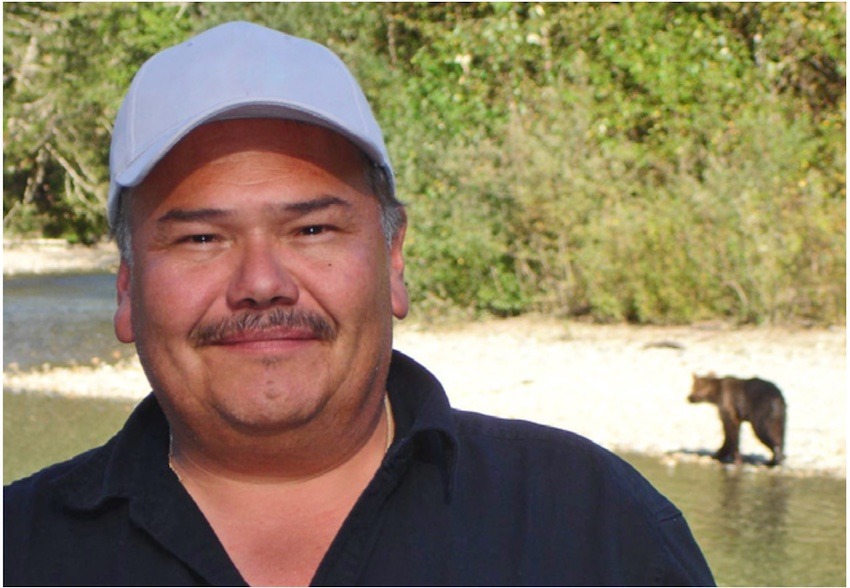

Tom Sewid, from the Kwakwaka’wakw First Nation whose territory spans northeastern Vancouver Island and the adjacent mainland inlets, is the president of Pacific Balance Marine Management Inc. This indigenous organization intends to restart a seal and sea lion harvest on the west coast and has presented a detailed harvest plan to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. The plan is titled Indigenous Commercial Harvesting of Pinnipeds in British Columbia: Applying Indigenous Ecology for Management and Economic Opportunity.

Tom Sewid

This excerpt from the document explains the cultural connection between coastal First Nations and these mammals; underpinned by the creation story that is foundational for coastal First Nation’s beliefs and actions:

“Our indigenous ecology places humans inside the ecosystem and thus our interactions with the environment are integral to our role as balacers of the ecosystem.”

Sewid explains that the removal of First Nations from this balancing role has significantly contributed to the increase in pinniped populations.

“We now see seals and sea lions miles up rivers and in lakes where they have never been seen before.”

Captain William Spring (Courtesy University of Victoria)

It took Europeans a while to recognize the economic benefits of sealing. William Spring of Victoria is credited with the first BC seal hunts which took place in 1865 off the west coast of Vancouver Island. During the 1880s, sealing was big business in Victoria, with schooners operating as far afield as the North Pacific and the Bering Sea. This was known as “pelagic” sealing.

By 1895, the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans “reported that 65 vessels, with a total tonnage of 4,192 tons and valued at $643,000, were registered in Victoria and Esquimalt harbours, employing 807 whites and 903 Indians.” The Victoria sealing industry resulted in “8,500 residents directly dependent on an industry with $750,000 in annual revenues” (BC Commercial Fishing, J.F. Forrester 1975).

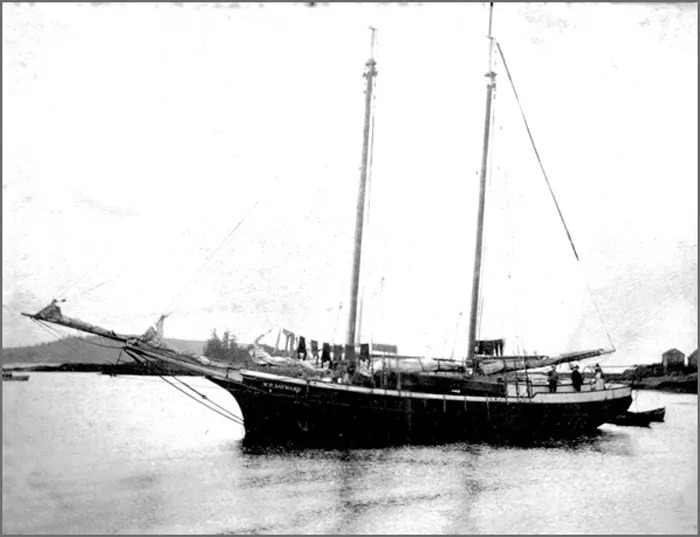

[Visit Victoria Harbour History for accounts of The Vagabond fleet and Victoria’s early sealing vessels and industry such as this picture below from this website]

Victoria Harbour History: “Sealing schooner ‘W.P. Sayward’, built on Laing’s Ways Accreditation: Ruth Laing and her late husband, Walter Laing (great grandson of Robert Laing) of Victoria”

My paternal great-grandfather, Alexander Ross, co-owned of one of those vessels. In 1896, he was caught up in an international intrigue, when his sealing schooner was seized by the Russians. In 1899, he petitioned Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier over U.S. efforts to remove foreign sealers from the Bering Sea. In his letter to the prime minister, he wrote: “The U.S. government is agreeable to pay the owners of sealing vessels a sum of one hundred twenty five dollars per ton… This is a small pittance to relinquish such an important right for all time to come.”

While pelagic sealing disappeared coastal commercial sealing was encouraged, particularly by fishing interests who saw seals and sea lions as competitors for the salmon resource. Sealing activity over the first half of the 20th century drove coastal populations of both seals and sea lions to low levels, prompting the implementation of commercial sealing bans in 1970—which remain to this day.

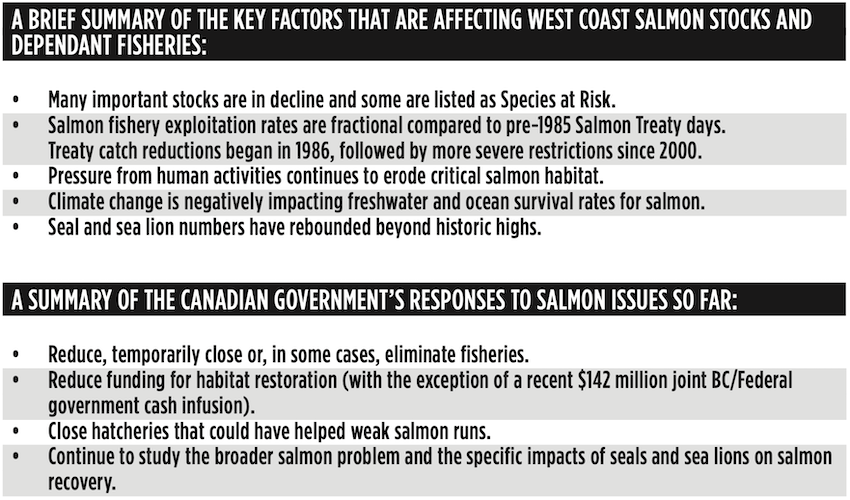

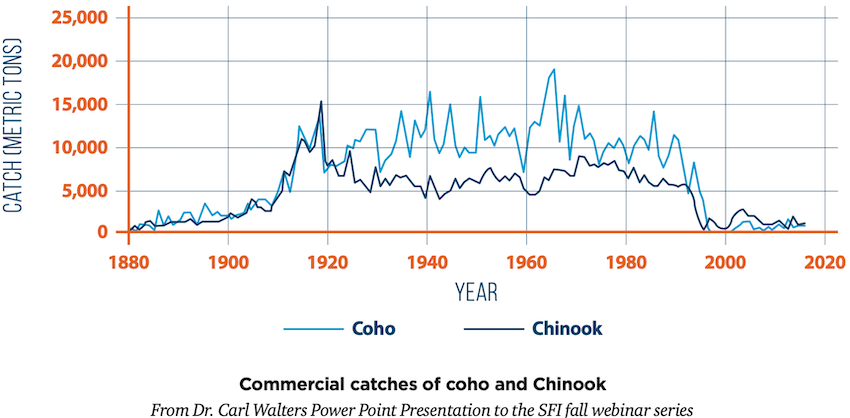

The Connection To Pacific Salmon

Current population data shows that seal and sea lion populations are very healthy and have been for decades, raising this question: Do they still require the same level of protection? Additionally, salmon populations are not healthy, and they need a comprehensive recovery plan that goes far beyond salmon catch reductions. Should a seal and sea lion harvest be part of that comprehensive plan?

Seals awake to the sound of a fishing reel

The environmental community is still opposed to the commercialization of seal hunts. But there are degrees of opposition that muddy the waters. For example: Greenpeace has apologized for their position on seal hunt bans that devastated northern Inuit communities for decades, and it now accepts traditional harvest for sustenance and sale. However, other groups have come out against this First Nation harvest restart proposal.

There is growing evidence from research in the U.S. and Canada that the current population of seals and sea lions is having a significant adverse effect on salmon recovery.

Dr. Carl Walters, professor emeritus at UBC Oceans & Fisheries, provided this quote:

“We can’t say for sure that reducing seals will restore the Georgia Strait fishery (to its original leves), but we can be pretty sure that my favorite fishery will not recover if nothing is done.”

There are significant differences between the current situation and the hunts that occurred in the 19th and 20th centuries. First, the northern fur seal hunt was driven exclusively by economic considerations. Second, the 20th century coastal hunt was based on removing competition for salmon and improving salmon fishing revenues. Third, by 1970 seal and sea lion numbers had been driven to low levels, but salmon stocks were still relatively productive, and would remain that way for nearly two decades.

Dr. Carl Walters

Fourth, this is exactly opposite to the current situation where seal and sea lion populations are at record highs and key salmon populations are at record lows, as are salmon fishery exploitation rates. Fifth, economic survival, not greed, is a key driver. Finally, the most immediate imperative is to prevent critically important salmon runs from failing or, even worse, extinction.

Dr. Walters has done considerable work on assessing this problem and his conclusions are sobering.

• Based on population reconstruction work done by Peter Olesiuk seal and sea lion numbers are currently far larger than in the preceding 140 years.

For example, the 2019 seal population topped 100,000, with approximately 40,000 in the Salish Sea. The previous high population estimate was 60,000 in 1890, falling to a low of 20,000 in the early 1960s.

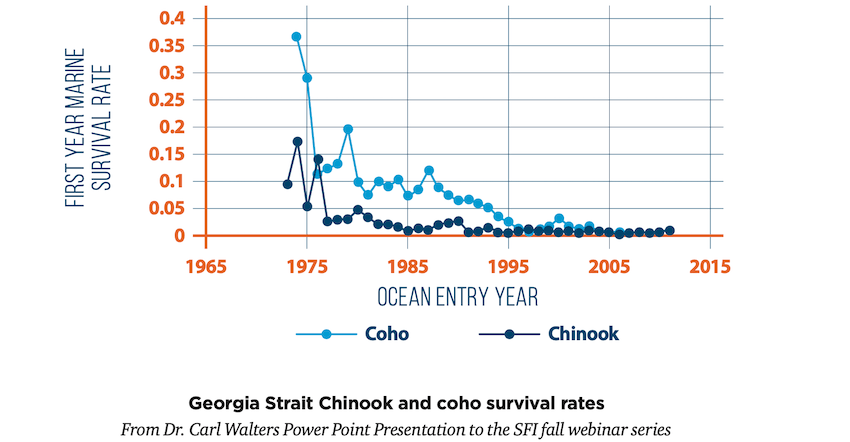

This graph shows a direct correlation between serious declines in Chinook and coho first ocean year survival rates and the start of a steady 25-year seal and sea lion population increase in Georgia Strait.

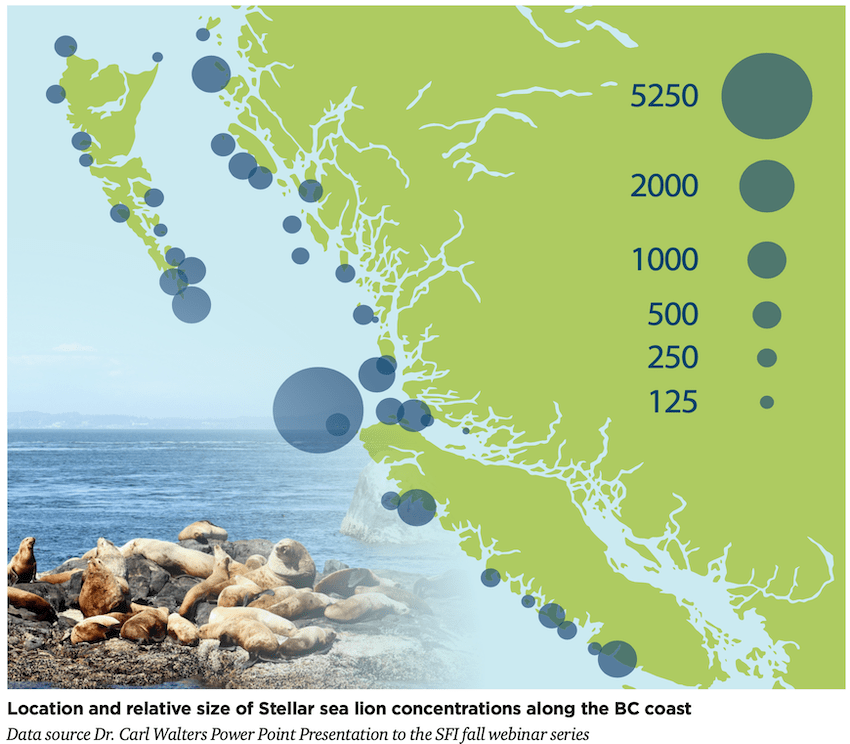

- Direct estimates of potential sockeye consumption by sea lions now imply predation mortality rates as high, or higher, than fishing mortality rates.

- Adult sockeye migrate past the largest Stellar sea lion populations in BC.

There is a concentration of larger sea lion haul-outs at and adjacent to the northern tip of Vancouver Island. This is a salmon choke point, as they either pass down the inside waters or along the west coast of Vancouver Island on their homeward migration.

Peter Thor (on Westcoast Fishermen Facebook Group) “Below is one the Sea Lion did not get. Tough to make a living competing with pinnipeds”

Supporting studies from Puget Sound, such as Impacts of Pinnipeds on Chinook Salmon (Pamplin, Pearson & Anderson), indicate significant seal and sea lion predation of juvenile Chinook salmon, once they enter the lower river and near shore marine environments.

November 6, 2020 – Dr. Carl Walters – Role of marine mammal predation in recent B.C. fishery collapse

Is There a Solution?

There may well be, but it might generate controversy, unless saner heads prevail. The best course of action requires that the most up-to-date science be presented impartially, and that all of the cause-and-effect scenarios within the entire ecosystem be evaluated.

Dr. Walters is a supporter of re-starting First Nation’s seal and sea lion hunts, but he also recognizes that this would be controversial, and recommends quickly reducing seal and sea lion numbers. Harvest opponents counter that a big cull is too risky, the support data is insufficient, salmon are a small percentage of yearly seal and sea lion diets, seal hunting is inhumane, and removals poses a risk to transient whales.

Conversely, seal hunts remove competition for salmon that are required by endangered Southern Resident Killer Whales.

The current Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) position on First Nations’ access to seals and sea lions was explained in an email from Lara Sloan, the DFO’s communications director. DFO acknowledges the significance of these species for food, social, and ceremonial First Nations purposes (FSC), and access under these conditions is permitted. Currently, however, there is no commercial pinniped harvest on the west coast. Any proposals for a commercial harvest must meet criteria set out in the DFO’s New & Emerging Fishery Policy, and this is a multi-year process. The priority is to ensure the best science is considered when assessing the role of seals and sea lions in sustaining a healthy aquatic ecosystem; and currently DFO does not use seal and sea lion culls as a means of managing pinniped populations.

The First Nations harvest plan is comprehensive and worth reading. It proposes to strike a balance by offering a three-stage plan beginning with a period of small demonstration harvests lasting 1 to 2 years, then moving to the harvest reduction period over 4 to 5 years. This stage is intended to bring the numbers within a healthy and sustainable abundance range. Beyond the first 5 to 7 years, the harvests would be based on keeping the pinniped population within that range.

So is the seal and sea lion story a success or an impending disaster? It could be both, but the potential for a positive outcome exists if there’s a will to arrive at balanced and less emotionally charged solutions.

Fish chased and eaten while sportfishing near Comox BC

For information on the harvest plan contact Tom Sewid at tom.sewid@gmail.com or ask to join the group on Facebook.

This article appeared in Island Fisherman Magazine. Never miss another issue—subscribe today!

2 Comments

Leave A Comment

Visit the Store

$34.99

$34.99

Featured Catch

Joel Unickow halibut (Photo: Rob Frawley Lucky Strike Sportfishing Tofino)

No doubt about it. Let the harvest begin. Money, food and pelts for the First Nations. Pelts for the tourists. A great boost for economy. Life saving for the dwindling race of wild salmon. Common sense. But remember we are dealing with Fisheries and Oceans Canada and PETA.

I hope that this happens and succeeds.