Although only slightly larger than a grain of rice, the full-duplex, passive integrated transponder (or PIT) tag packs an impressive scientific punch. Passive Integrated Transponders (PIT tags) are tracking tags activated by a nearby antenna. These tags contain a microchip that, when triggered, transmits an ID signal to the antenna’s connected computer, recording the tag’s identity and the time of the encounter.

Developed in the early Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries’ scientist Earl Prentice, the PIT tag was initially envisioned in fisheries use for tagging individual spot prawns for a study assessing aquaculture potential. The need for a small, biocompatible transponder which could be implanted into an animal to both identify and track movement was also something that researchers were looking at for horses and cows. So, using technology borrowed from a system in place to monitor railway cars, they began to figure out how to downsize the radio-frequency identification (RFID) technology to use in fish.

PIT tag tray and gun (Photo: James Costello)

The end outcome of those early efforts resulted in a 12mm by 2.1mm unit consisting of a ferrite core wrapped in copper wire which is then laser sealed in a glass cover. This tiny transponder holds a unique 14-character ID which, when “interrogated” by a powered antenna, will send a code to be recorded by a reader and logged.

Adding PIT tags to fish (Photo: James Costello)

The initial push for this new salmonid-friendly transponder came from a joint effort between NOAA and the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) in their efforts to measure fish passage in the Columbia River Basin, an effort that continues today with the PTAGIS database (https://www.ptagis.org), where data from more than 53 million tagged fish has been collected since 1987.

While the initial process involved printers and paper with lots of cords and headaches, today’s versions can be handheld, submerged on the river bottom as an array (via Litz cord), mounted within a fish ladder, or even mounted to a floating raft. All send their data to a digital storage unit which can then be exported to a computer at the researcher’s leisure and utilized to answer any matter of pressing scientific questions.

Antenna array designed by Jamieson Atkinson at the BC Conservation Foundation (Photo: Tom Balfour)

The Science Behind The PTAGIS Program

One of the most important questions being asked relates to the survival of hatchery raised salmon as they make their way out of the river and into the ocean, which the aforementioned PTAGIS program has sought to answer for decades. During their “outmigration,” these fish will encounter both natural and man-made challenges depending on where they are, and in the Columbia system both are significant, with dams being one of the most concerning impacts.

Closer to home, an application was found in the traditional territory of the Toquaht Nation, located near Ucluelet. Effects of release size, location, and timing on the freshwater residence and early survival of Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytcha) on the west coast of Vancouver Island, a MSc thesis by Tom Balfour at UNBC completed in 2023, sought to answer some key questions related to fish size and location of release, namely to “assess the viability of utilizing alternative release sites to enhance survival and achieve a more equitable distribution of fish throughout the available habitat.”

With support from the nation, fry reared at the Thornton Creek Hatchery taken from wild Toquaht River brood-stock in 2021 were raised until they were large enough to be safely implanted with PIT tags—usually a minimum of 69mm or more, which is about 2g and close to the minimum release size for most hatchery Chinook, although much larger than many observed wild fry.

To facilitate the tagging, hatchery crew utilized a “clipping trailer” provided by the DFO, which contained a number of stations set up to have multiple staff working simultaneously. The fish were anesthetized before using a Biomark MK25 PIT Tag implanter to insert the tag into their abdominal cavity. After tagging, the small salmon were directed down a series of tubes which would place them in separate Capilano troughs for future monitoring.

Clipping trailer and cap troughs (Photo: James Costello)

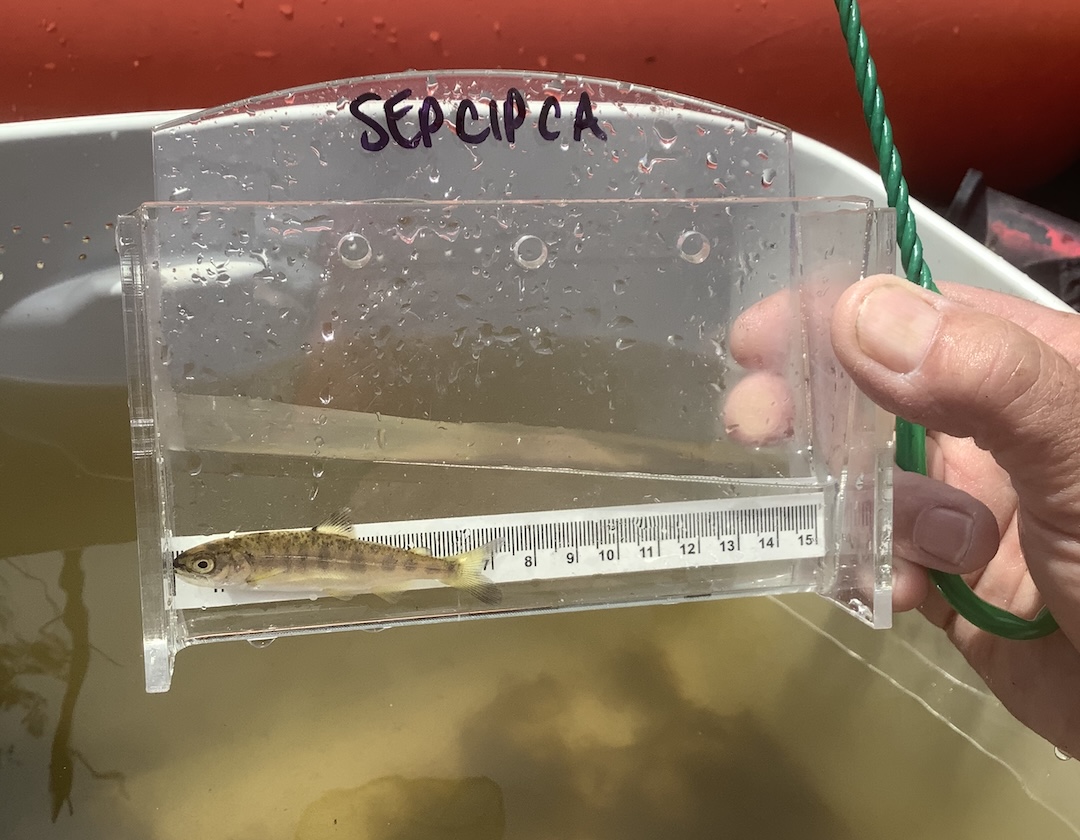

Close to 5,000 salmon fry were successfully tagged and kept at the hatchery for more than 40 days afterwards to ensure that they had retained the tag and were in good health prior to release. In preparation for release, all fish were once again sampled for weight and length and their individual tags scanned and recorded to track the different groups during their upcoming outmigration.

Smolt sampling and scanning for tags (Photo: Tom Balfour)

While the work at the hatchery was ongoing, a crew began installing the antenna arrays which would record the passing smolts in the lower section of the Toquaht River. This flat, wide section of the river is prime chum spawning habitat in the fall and is within a couple kilometers of tidewater, making it “somewhat” accessible by boat, thereby facilitating the transportation of batteries, solar panels, cable antenna, and assorted gear needed to assemble the system. Two antennae were installed 100m apart, extending 100% of the channel width during low water conditions and covering 80% of the water column vertically, with a read range of roughly 25cm above the stream bed.

Transporting gear to site (Photo: Tom Balfour)

Crew transporting array gear

Once the arrays had been tested and tweaked for about a month, the timing was right to begin releasing the first groups of fish. On May 23, 2021, the first three batches of about 500 fish were transported to their respective release sites on the river system: Lower river, lake, and upper river. On June 9 and 19, two further releases were made at the three sites. By staggering releases over time, it was possible to get a wider range of release size, the later fish being the largest, as well as capturing a wider range of water levels and conditions.

PIT-tagged Chinook Data Observations

A total of 4848 PIT-tagged Chinook were released into the Toquaht system, resulting in 1021 unique tag detections between May 24 and September 1, 2021. From this data many interesting observations were made:

- A mean survival rate of 0.39% was seen.

- Minimum residence time (between release and crossing array) was 12hrs for lower-river fish, while the maximum was 61 days for a fish released in the upper river on the same day.

- Most fish passed the array between 11pm and 3am.

- Out of 1021 fish that were detected, 228 were lower-river-released fish, 398 were released in the lake, and 395 were released in the upper river.

- The highest detection rate was seen in the lake-released fish from June 19, at 42.8%, giving them a median survival probability of 0.70%.

- While the study points at a few encouraging results, which will inevitably educate future release strategies for Thornton Creek Hatchery, it also leaves many questions unanswered relating to predation and the physical aspects of the river itself. As study author Tom Balfour states: “The counterintuitive survival patterns observed in this study emphasize the intricate and variable nature of the factors and mechanisms influencing survival rates.”

Studies such as this are essential in increasing our understanding of salmonid behaviour and educating our enhancement efforts. While they often leave many new questions to be answered, they are a key part of the scientific process. Each step gathers more information and gets us further towards quantifiable improvements in our management of the natural environment. With the use of the tiny PIT tag, we have a good chance of answering some very big salmon questions.

Chinook fry to be tagged

This article appeared in Island Fisherman magazine. Never miss another issue—subscribe today!

Visit the Store

$34.99

$34.99

Featured Catch

Joel Unickow halibut (Photo: Rob Frawley Lucky Strike Sportfishing Tofino)