This article is written by Dr. Richard Beamish, an Order of Canada and Order of British Columbia recipient, and an internationally respected scientist and salmon researcher.

Background

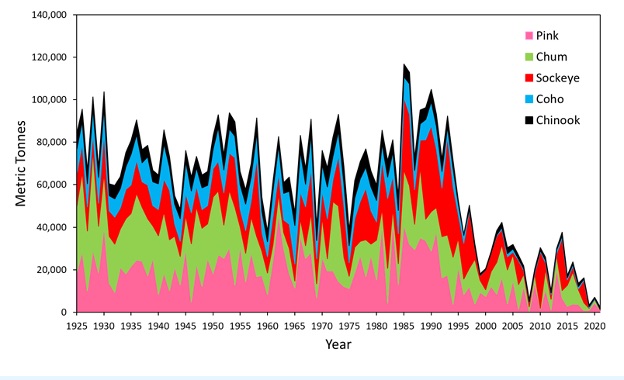

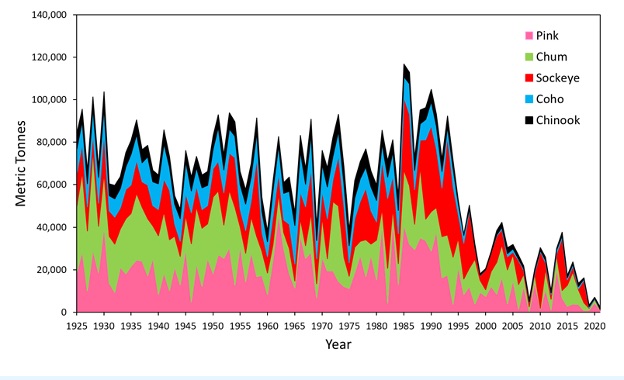

There are unprecedented changes occurring in the population dynamics of Pacific salmon across their north Pacific distribution. The BC commercial salmon fishery has collapsed with recent average annual catches only a fraction of those from 1970-2000.

The collapse of the commercial salmon fishery in British Columbia with the colours representing the different species. (Data Source: North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission (NPAFC). 2023. NPAFC Pacific salmonid catch statistics (updated July 2023). North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission, Vancouver. Accessed November, 2023. Available: https://npafc.org.)

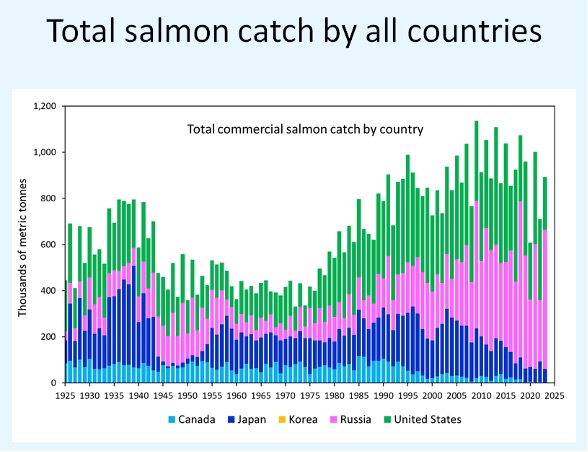

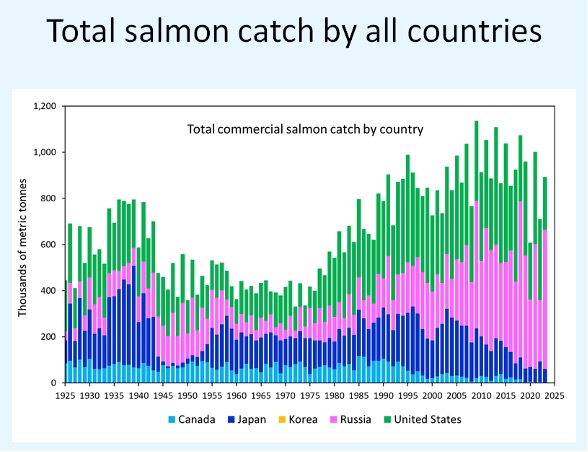

These collapses, which also extend to Japans’ fisheries, are occurring when there are more Pacific salmon in the ocean than at any time over the last 100 years.

The total catch of all species by all countries with the colours representing countries. (Data Source: North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission (NPAFC) 2023. NPAFC Pacific salmonid catch statistics (updated July 2023). North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission, Vancouver. Accessed November, 2023. Available:

https://npafc.org.) 2023 estimate is author’s preliminary estimate.

This is because salmon are surviving much better in the northern areas than the southern areas of their ocean distribution. Why this is happening is not understood. This means we do not have the science nailed down, as climate change continues to surprise us.

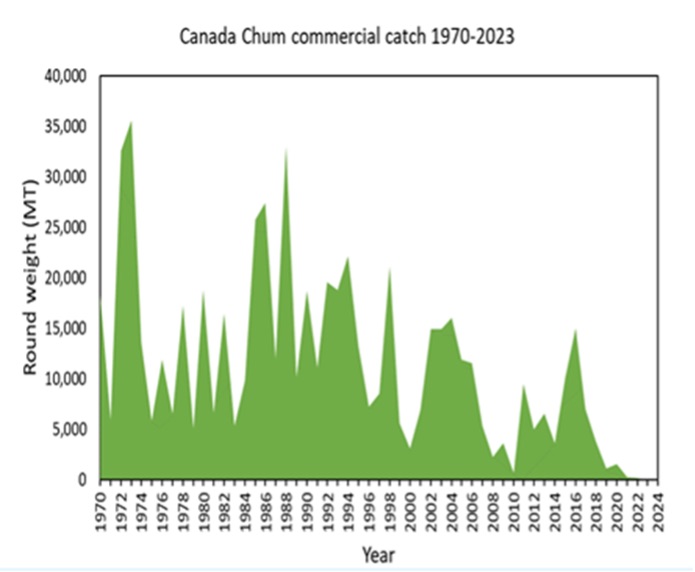

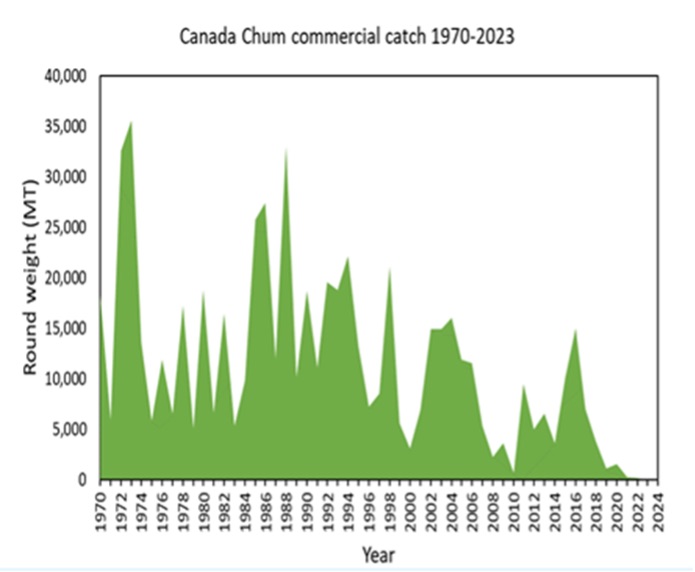

Past salmon abundance trends were previously used to indicate future salmon returns and fisheries management strategies. However, the ocean has a powerful influence on salmon abundance. Recent chum salmon declines are the best examples to show how these past understandings no longer are reliable for future stewardship. Chum salmon fry spend little time in freshwater, moving downstream to the sea almost immediately, where they remain in coastal waters until late summer or early fall. Then they migrate to the open ocean where they spend 3 or 4 years in the Gulf of Alaska before returning to their natal rivers. Optimum fry to adult survival rates vary from 1.8% to 3.1%.

Chum salmon fisheries were the largest commercial fisheries in BC, calculated by weight, with average annual catches from 1970-2000 of 15,063 tons. The fishery has now collapsed.

The recent collapse of the chum fishery in British Columbia. The declining trend is clear with the virtual collapse in the last few years. (Data Source: North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission (NPAFC). 2023. NPAFC Pacific salmonid catch statistics (updated July 2023). North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission, Vancouver. Accessed November, 2023. Available: https://npafc.org.)

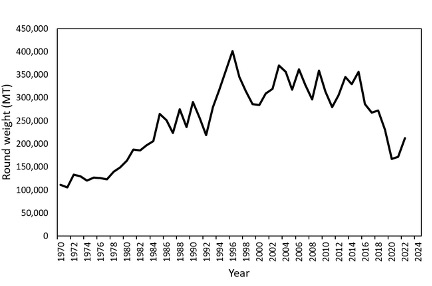

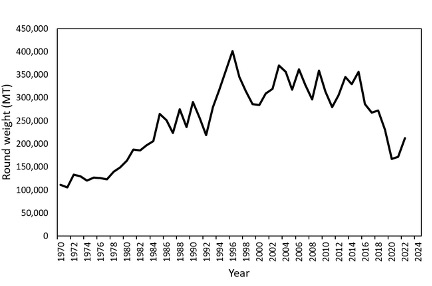

In 2021 the total catch was 260 tons, and in 2022 it was 180 tons. Spawning abundances have also collapsed in most areas: Nitinat chum are down 91%, Big Qualicum are down 90%, Cowichan are down 81% and the Fraser is down by 49%, all over the last 12 years. Alarmingly Chum salmon are no longer surviving well everywhere, and this is affecting catches by all countries.

The collapsing commercial chum fishery by all countries.

Winners & Losers

It is important to remember that Pacific salmon have survived ocean changes for thousands of years. So it might be expected that within the existing population structure there are some with an evolved resilience that allows individuals in the population to grow and prosper in the new ocean conditions. We just need the research to find and study these populations.

An example of evolved resilience is the 2023 return of Chinook to the Fraser River. The final Fraser escapement numbers are not in but the total return will be a record because of the exceptional abundance of south Thompson River Chinook populations. In 2010 our research group at the

Pacific Biological Station published our discovery that Chinook smolts from the south Thompson used Georgia Strait differently. They entered the strait 6 to 8 weeks after smolts from most other Chinook salmon populations, when the water was warmer and had less surface salinity.

We reported our discovery to the staff at the

Big Qualicum River Hatchery and they started releasing some smolts about one month after normal release times. Their delayed releases appear to be surviving better than the normal releases with the total Chinook returns in 2023 reaching a record high of 18,425. The exceptional ocean survival of late ocean entering smolts is an example of how an evolved resilience benefited from a change in the ocean that was apparently less beneficial to most other populations. The current success of this hatchery release is a good example of the importance of understanding the mechanisms that regulate ocean survival, and applying the scientific understanding to hatchery production.

Recent changes in Georgia Strait are also benefiting coho salmon. Coho populations began to decline in the late 1980’s. In the late 1990’s this decline prompted then Fisheries Minister, David Anderson, to close major inshore coho fisheries. Not much changed despite fishing closures until about 2007-2010 when a shift in ocean conditions produced more food for coho, resulting in bigger juveniles and better survival. In 2018 they began to over-winter in Georgia Strait, something that had not happened since the early 1990’s. In 2022-2023 there were large abundances that stayed all winter, resulting in the best coho fishing in 30 years in 2023. Last winter, coho were once again abundant in the strait which could produce even better fishing this summer.

The dramatic turnaround is related to a natural shift in the ocean that produced more food at exactly the right time for smolts that were entering the ocean. However why the ocean changed and what to expect remain to be discovered. We were able to understand some of the mechanisms related to the decline in coho survival in the 1990’s because DFO continuously supported a program that studied the ocean ecology of salmon in Georgia Strait since 1998.

The Secret Life of Salmon

We know some things about salmon in their first few months in the ocean, but we know very little about their lives once they enter the open ocean. It is this secret life of salmon that we need to understand. Fresh water is relatively safe for salmon to reproduce, but it is the ocean where their abundance is mostly determined. I wanted to find out more about the winter ecology of salmon in the Gulf of Alaska, so Brian Riddell and I privately raised millions of dollars to charter ships in the winters of 2019, 2020, and 2022. The first charter was on the famous Russian research vessel, Professor Kaganovsky, which was arranged for our use by the Russian Fisheries Minister.

The famous Russian research ship, Professor Kaganovsky at the dock in Vancouver in 2019. Photo Credit: Laurie Weitkamp, NOAA.

Our researchers were all volunteers and we received help from many people and organizations, like the Pacific Salmon Foundation.

Volunteer investigators from Korea, Japan, Russia, United States and Canada at sea on the Professor Kaganovsky. Photo credit: Chrys Neville.

We made a number of important discoveries:

- First ocean year Fraser River Sockeye migrated as far as the Asian side of the Pacific Ocean.

- There were fewer 2nd, 3rd and 4th ocean year BC chum salmon compared to similar aged chums from Japan, Russia and Alaska. Perhaps because BC chums did not store enough energy (lipids) to survive the winter.

- Chum and coho form schools in the winter which improves their survival (see below image).

- Our catches of steelhead show they are very susceptible to ocean warming because they occupy the warmer top few meters of water.

Evidence that chum salmon from rivers thousands of km apart are genetically programmed to find other chum salmon in the Gulf of Alaska in the winter. DNA from these salmon showed that they originated from rivers from northern British Columbia to Alaska. The study in 2022 used Japanese experimental gillnets to sample for salmon in the winter in the Gulf of Alaska.

Other changes include record abundances of pink salmon throughout the North Pacific, and record returns of Sockeye to Alaska. These record abundances are also associated with alarming decreases in size of fish in most populations of all salmon species. The important message is the changes that are occurring are unprecedented and are most certainly related to climate change impacts on the ocean. Thompson River Chinook and Georgia Strait coho show that Pacific salmon species contain populations that have abilities to survive, and even prosper, when ocean habitats change. We need to discover these populations for all species of salmon and identify the specific mechanisms responsible for their better survival.

Dr. Richard Beamish, an Order of Canada and Order of British Columbia recipient, and an internationally respected scientist and salmon researcher.

It is not an exaggeration to say that the general health of salmon is an index used by British Columbians to measure how we are doing as stewards for all plants and animals. Governments recognize this and direct resources towards sustaining and rebuilding salmon runs. However the reality is that rebuilding in the recent environment of ocean change requires a better understanding of what I called the ‘secret life of salmon’. Hitting the reset button on our thoughts about salmon may allow the collective energy of those concerned about salmon to work together. This requires discovering what we need to be responsible stewards of Pacific salmon in the face of climate related habitat changes.

Great to get a little real info !dfo seems only to do fishery closures and allocation not research into what is acctually happening.we need on water research to provide data,not just sitting at computer models of old systems.thanks for your passion for fish

2023 saw the largest population of Coho I had seen in 30 years in Area 12. 2023 saw the largest run of Chinook I had seen in 30 years in Area 12. Repeated calls to the DFO to allow retention of Coho after August 1 was dismissed, repeated calls to the DFO saw them not allow retention of Chinook until July 15 and then was restricted by size. Until August 15. There has to be another system that recognizes in, times of abundance a retention fishery is allowed. We no longer take 30 Chinook. We are allowed 1 a day in inside waters, 10 per season, we will not devastate the stocks with those numbers.

Thank you Dr Beamish for such an informative article!. I have read many of your papers and articles over the years and found them an excellent source of information and scientific excellence!