A newly published study casts doubt on the popular belief that a lack of Chinook is one of the main causes for a decline in the southern resident killer whale (SRKW) population. In fact, research found that the density of prey fish like Chinook actually was 4–6 times higher in the southern resident habitat than in the northern habitat.

Mei Sato and colleague studying SRKWs

The study, “Southern resident killer whales encounter higher prey densities than northern resident killer whales during summer,” was published by Canadian Science Publishing (Canada’s largest international science journal publisher) on Oct. 12. The authors—Mei Sato and Andrew Trites from the UBC Marine Mammal Unit and Stephane Gauthier from the Institute of Ocean Sciences, Fisheries and Oceans Canada—reported their “findings do not support the hypothesis that southern resident killer whales are experiencing a prey shortage in the Salish Sea during summer and suggest a combination of other factors is affecting overall foraging success.”

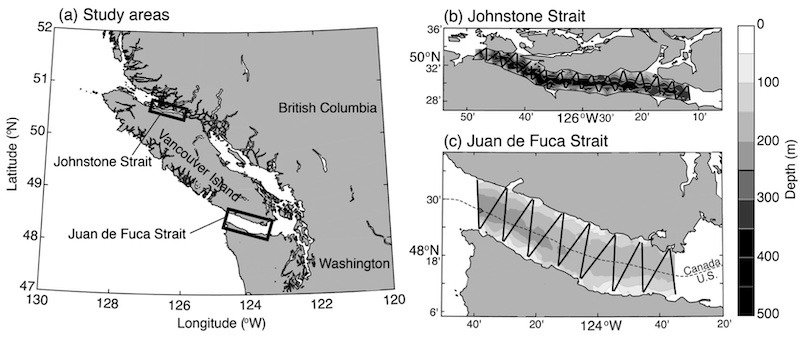

(a) Study regions in the Northeast Pacific where southern and northern resident killer whales prey on migrating Chinook salmon. (b, c) Representative transect lines and bathymetry contours are shown for each study area. The survey area in 2018 was limited to Canadian waters.

Andrew Trites

Professor, Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries

Associate Member, Department of Zoology

Director, Marine Mammal Research Unit

Here is the background: Wild Chinook were in decline, and some orcas seemed emaciated and starving, and so the conventional wisdom became that the former was causing the latter. By 2016 the messaging to support this was at times strident, particularly from activist environmental organizations in Canada and the US, who leveled pressure on regulatory agencies in both countries to close fisheries, clamp down on whale watching, and create large areas that excluded all marine activities.

They also mounted an effective orca campaign through seminars and media, while using images of peanut heads, the name applied to emaciated orcas, to amplify the “no Chinook” message. A graphic video of a female orca pushing her dead calf and news stories showing researchers trying to feed Chinook to orcas conveyed powerful messages for the public and decision makers to absorb. How could you not do everything possible to save these iconic mammals?

SRKW photo courtesy Joel Unickow, Island Fisherman

When governments did act, the southern resident orca protection regulations were extensive, affecting almost all marine activities, like whale watching, vessel traffic movements, angling, commercial fishing and vessel speeds within designated critical foraging habitats. The changes were buttressed by expanded approach distance rules and progressive closures of substantial portions of water to all marine uses.

UBC Scientific Fishing Vessel, Tom Davis and Rob Marshall Juan de Fuca

The UBC study used various fishing methods, recreational and commercial, to develop a system for identifying larger Chinook from other fishes that showed on the team’s ultra high-powered sonar devices. (Full disclosure: I participated for one day in the 2018 Juan de Fuca Strait study). Other data collection occurred in Johnstone Strait, part of the northern resident orcas’ feeding territory.

These quotes from the study explain the key conclusion:

“We assessed the spatial variability of large fish as potential prey for northern and southern resident killer whales. Contrary to our hypothesis prey densities were higher in southern resident habitat than in northern resident habitat. The 4-6 times higher density of prey available to southern residents, when compared to northern residents, suggests they were not limited by prey in the summer.”

Jason Assonitis of Bon Chovy Fishing Charters with winter Chinook caught in the Southern Gulf Islands – Photo courtesy Gibbs Delta Tackle

Jason Assonitis, owner of Bon Chovy Charters, is not surprised by the results. Assonitis was acknowledged in the UBC report for helping to set up the test boat for fishing the study areas. “Media, ENGOs, and government were pushing the narrative that we were down to our last Chinook in the Salish Sea,” he says. “I average 150-200 days on the water [per year], and we were seeing some of the best Chinook numbers in our lifetime over the last handful of years.”

Owen Bird, SFI Executive Director

Owen Bird from the Sport Fishing Institute is pleased with the UBC findings. “The study makes it clear that rather than fishery restrictions, the avoidance of southern residents and noise or disturbance is a more impactful contribution to recovery,” he says. “We are glad the UBC team chose to explore this question of prey abundance and availability.” He also encourages anglers to continue to abide by the avoidance regulations and recommendations.

Chris Bos is president of the South Vancouver Island Anglers Coalition. This volunteer group has raised and released 2.5 million Chinook to help feed southern resident orcas using their own funding sources.

SVIAC Chinook Pen Rearing Site To Help Feed SRKW Photo Courtesy Glen Varney

Chris says he is happy with the findings, but points out local anglers knew Chinook were abundant in Juan de Fuca Strait because of large numbers of fin-clipped US hatchery Chinook. Yet he is puzzled by the recent ENGO push to close targeted marine Chinook fisheries and all salmon fishing in Chinook foraging areas from March 1 to December 1. He calls it “a nonsensical, ideologically driven idea, based on anti-fishing sentiment not science, which might be viewed as intentionally misleading government and the public.”

Anglers see this study as a much-needed baseline data reset that, minus the unnecessary drama around the issue, could lead to a recovery plan that gives these orcas a better chance at survival.

Visit the Store

$34.99

$34.99

Featured Catch

Joel Unickow halibut (Photo: Rob Frawley Lucky Strike Sportfishing Tofino)