What we find in the stomachs of our catch is a frequent subject of conversations—in the boat, over beers, or online. As a former guide and lifetime angler I have participated in many such conversations, and as a fishery scientist I have had the opportunity to discuss what I have learned in these conversations with colleagues. Sometimes what is common knowledge to anglers comes as a surprise to scientists, adding support to an existing theory or suggesting a new avenue for research. Unfortunately, it is tough to incorporate “fish stories” into the scientific process. What is needed is data—standardized, validated, and thoroughly documented. With the help of salmon anglers throughout BC, University of Victoria’s Fisheries Ecology and Marine Conservation Lab are working to compile such data. The stomachs of your Chinook and coho salmon are no longer just crab bait; they can help us understand the ecosystem that supports our salmon resource.

It is no secret that our understanding of marine ecosystem function is imperfect.

Why did marine survival of Strait of Georgia Chinook, coho, and steelhead crash in the early 1990s? Why are some stocks apparently recovering (e.g. Cowichan Chinook), while others are still in big trouble (e.g. Upper Fraser Chinook)? Why did coho vanish from their traditional summer feeding grounds in the northern Strait of Georgia for nearly two decades, then reappear in 2013 (and intermittently since)? To answer these questions, we need to understand how the marine ecosystem works and how it is changing.

How do we understand the changing marine ecosystem?

Since 2017, we have been working with participants in British Columbia’s public fishery to sample the diets of adult Chinook and coho salmon. The way the program works is simple: Participating anglers remove, bag, and freeze the digestive tract (stomach and intestine) of their catch, recording catch details on an accompanying card. A number of leading charter operators have also found time in their schedules to collect samples, including Bon Chovy and Pacific Angler in Vancouver, Mark Grant’s Sport Fishing in Sooke, Twin Strike Charters at Rodger’s Lodge in Winter Harbour, Island Pursuit Sport Fishing in Comox, Gulf Rascal Charters in Pender Harbour, Brightfish Charters and Jeremy Maynard in Campbell River, and Langara Island Lodge in Haida Gwaii.

Back at our lab, the digestive tracts are analyzed in detail.

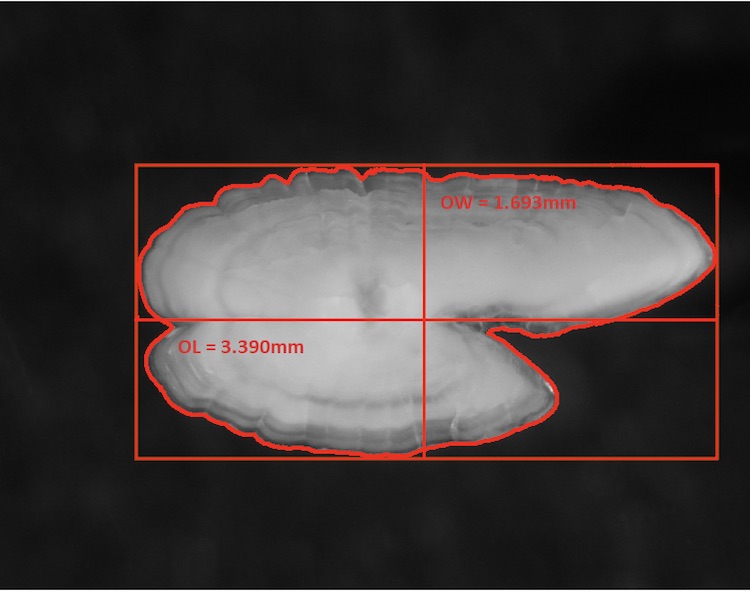

Stomach contents are identified and weighed, and samples are taken for biochemical analysis. Prey fish otoliths (ear bones) are removed and can later be used to determine age, calculate length of digested prey, and even to study growth rates and migration history. We also take samples to send off to other researchers. So far, we have been sending muscle from herring to the University of Washington, where geneticists will try to determine which spawning populations are contributing to salmon diets. We are also sending sand lance to DFO, which is studying how plastic particles enter the food chain. We don’t stop with the stomachs. We identify the fish bones, squid beaks, and worm jaws that collect in the intestines, providing us with information even for fish with empty stomachs. We are constantly improving our methods and trying to make sure the information and samples we are collecting will be valuable to as many researchers as possible.

Prey fish otoliths (ear bones), like this one from a herring, can be used to determine size, age, growth rate, and even migration history.

What have we learned so far?

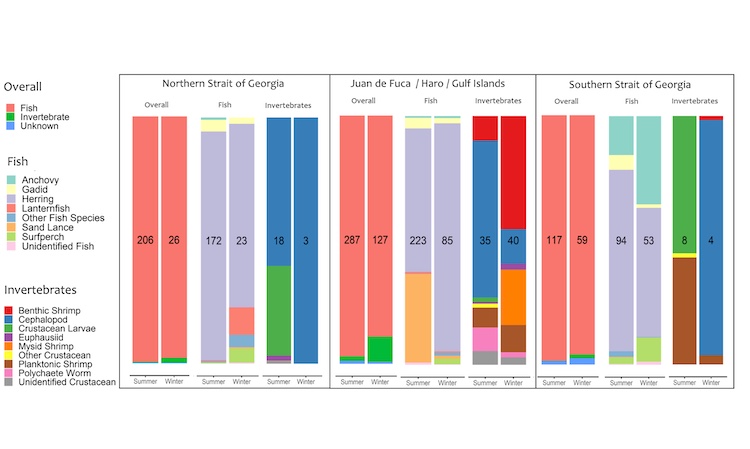

It will come as no surprise to Vancouver Island anglers that herring are overwhelmingly the most important prey for Chinook and coho. Juvenile herring are important year-round, while mature herring are important in the Strait of Georgia primarily in spring and summer. The genetics and otoliths of these “resident” herring may help us understand more about what makes a herring stay in the Strait of Georgia, a question which has puzzled both anglers and scientists for many years.

Herring are not the only prey fish; there are also interesting patterns in the occurrence of other species. Northern anchovy, which recently reappeared in the Strait of Georgia after a long absence, are important in diets in Howe Sound, the lower mainland, and the southern Sunshine Coast, but are almost totally absent elsewhere. Sand lance are a big part of spring and early summer diets in Haro Strait, Juan de Fuca, and Haida Gwaii, but are almost absent in the northern and southern Strait of Georgia. Other interesting species that are encountered less frequently include sticklebacks, shiner perch, eulachon, northern smoothtongue, barracudina, stubby squid, and juvenile pink, chum, and Chinook.

A mixed bag—lanternfish (top two), herring (middle), and eulachon (bottom) from a winter Chinook off Campbell River.

It is standard fishing knowledge that big lures catch big fish, and sure enough we find that bigger salmon eat bigger prey. The largest prey item encountered to date was a 29.6-cm (11-in) gadid (likely a hake) from a 96-cm (37-in) Chinook caught in Campbell River in June (maybe it’s time to put hooks on your flashers!).

We are excited about our results so far, but the biggest value of this program will be the ability to detect and understand changes in the ecosystem. To ensure success in the long term, we need to continue to connect with interested anglers who are willing to help. We are particularly interested in engaging anglers who fish year-round, as it is challenging to obtain samples outside peak fishing times.

Chinook diets by weight in different regions around Vancouver Island. Numbers printed over the bars indicate the number of samples to date. (click to enlarge)

It is easy to participate, here’s how.

When you catch a Chinook or coho, carefully cut out the whole stomach and intestine and bag it with a piece of paper recording (at a minimum) date, location, species, length, and adipose status (for more detailed instructions contact us by email). Freeze the stomach right away, and drop it off at one of the depots listed at the end of this article (please talk to staff to make sure your sample is put in the right place; not all staff may be familiar with the program) or contact us directly to arrange pick-up or drop-off. You can also pick up zip lock bags and waterproof data cards from totes in the freezers at depot locations (although scrap paper is fine too), or contact us and we will mail them to you. Thanks to the generosity of Islander Reels, each stomach submitted in 2019 will count as an entry in a draw for an Islander MR2 LA mooching reel (congratulations to Rick Hackinen of Campbell River, who won the 2018 draw).

Congratulations to Rick Hackinen of Brightfish Charters in Campbell River, winner of draw for an Islander MR2 LA in in 2018. Thank you to Islander Reels for their donation to our program. The 2019 draw will be held early in 2020, each stomach with accompanying data is one entry!

You can check out updates on the program on our Facebook page www.facebook.com/Southern-BC-Adult-Salmon-Diet-Program-493763831003993/ and contact us with your questions or comments at juaneslabmanger@gmail.com.

Many thanks to all the anglers who have supported the program so far, our funders (Pacific Salmon Foundation, WWF Canada, and DFO Stock Assessment) and to all our current depot locations.

Current Depot Locations

- Island Outfitters (Victoria)

- Home Hardware (Sidney)

- Harbour Chandler (Nanaimo)

- Tyee Marine (Campbell River)

- Pacific Net and Twine (Parksville)

- Bon Chovy Charters (Granville Island)

- Stillwater Sports (Ladner)

- Pacific Angler (Vancouver)

- Bamfield Mercantile and Marine (Bamfield)

- Ucluelet Aquarium (Ucluelet)

Added September 28, 2019:

- Esquimalt Anglers Clubhouse (Esquimalt)

- Powell River Outdoors (Powell River)

- Chapman Creek Hatchery (Sechelt)

Will Duguid, M.Sc., is a member of the Department of Biology at the University of Victoria.

2 Comments

Leave A Comment

Visit the Store

$34.99

$34.99

Featured Catch

Joel Unickow halibut (Photo: Rob Frawley Lucky Strike Sportfishing Tofino)

Hello

I am the program director for the Golden Rods and Reels fishing and Conservation club. We have a speakers program and would be delighted if you could a give a presentation to club members. We have between 25 -30 members and meet in Victoria at 2340 Richmond Rd. For more info. go to goldenrodsanreels.com

Hi Robert, We would be pleased to present to your group! I have sent you an email, I look forward to hearing from you

Will